Description

Susan M. Rossi-Wilcox

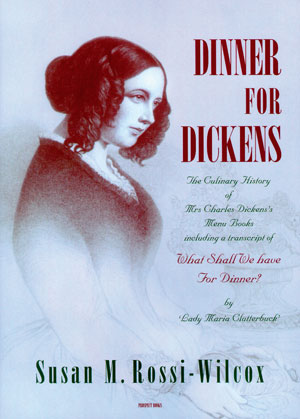

Dinner For Dickens

The culinary history of Mrs Charles Dickens’s menu books

| Catherine, the wife of Charles Dickens, was herself an author, but of just one book: What Shall we Have for Dinner? Satisfactorily Answered by Numerous Bills of Fare for from Two to Eighteen Persons. As the title indicates, it was a cookery book, in fact a pamphlet containing many suggested menus for meals of varying complexity together with a few recipes. It went through several editions after 1851, under the authorial pseudonym of ‘Lady Maria Clutterbuck’ with a brief introduction that was, commentators aver, the work of Charles Dickens himself. In this book, Susan Rossi-Wilcox has investigated the life of Catherine Dickens, the domestic arrangements of the Dickens family, the composition of this menu-book and how the various changes in succeeding editions reflect both Catherine’s own development and the state of play in Victorian cookery, entertainment and food supply. At the same time, it contains a transcript of the menu-book itself and the appendix of recipes. It would not be sensible to claim the little book changed very much about Victorian cookery, but it serves as a potent marker of what was going on at the time, for example the modes of service, the sorts of dishes cooked, the domestic organisation necessary to maintain a reasonably well-off household. Catherine Dickens herself is a very interesting character and this book has much to offer people seeking to get behind the façade thrown up by Charles Dickens and his biographers (the couple separated in 1858 and Catherine suffered from much negative spin). Susan Rossi-Wilcox paints a sympathetic portrait of a capable and resourceful woman. Dinner for Dickens is fully referenced and illustrated with contemporary photographs, drawn largely from the collections of the Charles Dickens Museum in Doughty Street, London.

Susan M. Rossi-Wilcox is a Curatorial Associate of the Botanical Museum of Harvard University where she is Administrator for the Glass Flowers Collection. |

Review by Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian (03/04/05)

Review of Dinner for Dickens by Paul Schlicke in The Dickens Quarterly (07)

Review by Kathryn Hughes in The Guardian ( 3 Apr 2005)

The sole of discretion

Catherine Dickens is the patron saint of first wives, everywhere. She was courted young, by a man on the make who used her plump, comfortable ways to win him a wide circle of useful friends. While he wrote and fretted and pushed, she bore him 10 children, coped with the death of one, and made sure that they all stayed quiet while the great man beavered away in his study. And then, just when she was past the age of even average prettiness, he dumped her for a girl the same age as their eldest daughter. Obliged to live with the stigma of separation from the man she still loved, Catherine also had to bear the worry of seeing her financial settlement nibbled to the point where it would only just do. And, as if that weren’t enough, over the last century and a half she has been obliged to watch from Heaven – hopefully a Dickensian paradise of simple cheer and apple-cheeked children – while many of her husband’s biographers systematically set about turning her into a dull frump with whom no man of genius could be expected to keep faith.

There are many ways of unpicking this damning narrative, but American scholar Susan M Rossi-Wilcox has chosen to do it by means of Catherine’s capacities as a housekeeper. For while Dickens, in that sour, post-separation phase, was apt to imply that she was as bad at this as she was at everything else, Rossi-Wilcox has delved into Catherine’s domestic records to show a woman passionately engaged with the whole business of keeping a good table (and, by implication, a good pantry, still-room and kitchen too). Instead of a domestic dowdy, reliant on a small repertoire of early to mid Victorian staples, Rossi-Wilcox finds a sprightly intelligence keen to graft dishes learned while living abroad in France and Italy on to a stock of sturdy “Scotch” staples that reflect a much-loved Edinburgh childhood.

The reason that Rossi-Wilcox can even attempt to do this is that Catherine’s manuscript menu books have survived (ironically because they belonged to the first wife of a great man) together with the odd fact that in 1852 she published a pseudonymous recipe book entitled What Shall We Have for Dinner? which was re-issued, in altered form, right through to 1860. Buttressed by the kitchen inventory from 1 Devonshire Terrace, where the family lived in the 1840s, as well as scraps of information about the arrangements at Doughty Street and Gad’s Hill, Rossi-Wilcox is able to study Catherine’s household in a way that has historically been impossible for all but a handful of courtly kitchens.

In some respects the Dickens family table turns out to be typical of its type, that of a metro-politan household leapfrogging several sections of the middle class. There is the usual love of mutton, beef and pork, pork, pork (Catherine is thrifty and anything piggy is cheap) and the instinctive resistance to vegetables and salad, especially the near-diabolic tomato. But in other ways the Dickenses displayed a set of preferences and passions that were entirely their own, born out of personal history and intellectual persuasion.

Fish, for instance, was regarded by most mid-Victorians with a kind of horror. Catherine, by contrast, loved anything with fins and from her kitchen emerged a stream of dishes along the lines of stuffed haddock, codling with oyster sauce and stewed eels. Rossi-Wilcox puts this down to her Scottish childhood, combined with Charles’s Kentish heritage that was full of Whitstable oysters and Dover soles. But she also neatly links this in with the Dickenses’ ideas on social reform, not the least of which was that if the working class would only learn to eat from Britain’s rich sea farms they could be weaned off the bad bits of fatty bacon that they insisted on seeing as the ultimate treat.

Using domestic ephemera to prise open the Victorian middle-class household is an excellent idea. Rossi-Wilcox’s work as a museum curator has given her the requisite gimlet eye to sort out her dutch ovens from her bottle jacks, or know the difference between a copper mould and a tin one, without which a book like this quickly degenerates into sloppy nostalgia.

There are, however, problems with the fact that Rossi-Wilcox is working on the other side of the world from Catherine’s kitchen. For instance, Rossi-Wilcox disconcertingly refers to Mrs Beeton having published her Book of Household Management in 1865, which is indeed the date that a version of the book first appeared in the US. The fact that the original actually appeared in 1861 and was being written from 1857 may seem piffling, but is crucially important when you are conducting a finger-tip search of the mid-Victorian dining room. Over a period of any eight years — but those eight years in particular — foods fell in and out of favour, cooking techniques changed and new ingredients became available, shifting the middle-class eating experience in small but crucial ways.

The odd thing is that Rossi-Wilcox clearly knows this, since her careful readings of the various editions of What Shall We Have For Dinner? are all about tracking the way in which items such as mullet gradually took a central place on the Dickens’ London dining table, thanks to the development of the Great Western Railway as a link to the fishing grounds of Cornwall. These inconsistencies, combined with a number of misnamings and repetitions, suggest that a tighter edit would have produced a text worthy of what is, despite everything, an imaginative attempt to refocus personal, literary and cultural history through the bottom of a custard cup.

Review of Dinner for Dickens by Paul Schlicke in The Dickens Quarterly (2007)

Food is of central importance to Dickens. Perhaps the most joyous scene in all his fiction depicts the Cratchit family gathered round their spare Christmas feast, and Scrooge celebrates his reformation by purchasing the prize turkey and sending it to Camden Town to replace their scrawny goose. The opening paragraphs of Dickens’s first published sketch, “A Dinner at Poplar Walk”(December 1833), introduce Mr. Minns at his breakfast; the last words which he wrote, on 8 June 1870, the day before he died, were “falls to with an appetite” (The Mystery of Edwin Drood, ch. 23). He bitterly recalled how he sometimes went without his dinner in the Blacking Warehouse days, and how he tried to assuage his hunger by staring at the pineapples in Covent Garden Market (Forster 1.2.28). From the oysters and beef at Bob Sawyer’s party, Betsy Prig’s cowcumber, and Ruth Pinch’s pudding, to the tea in which Mr. Venus floats his powerful mind, the novels are full of memorable depictions of food, and Household Words contains a substantial number of articles on culinary arts, varieties of food, its availability, its adulteration, and many other related topics.

It is no surprise, then, that Dickens took keen interest in the meals served in his own home. His daughter Mamie recalled that when there were guests in the house, he would study the dinner menu, “And then he would discuss every item in his humorous, fanciful way with his guests … and he would apparently be so taken up with the merits or demerits of a menu that one might imagine he lived for nothing but the coming dinner” (M. Dickens 19). Just as the chaotic dinners which Dora serves to David epitomize the pitfalls of a marriage entered into with an undisciplined heart, so too the proper provision for “a very good appetite and an excellent digestion” is, in Dickens’s view, an infallible recipe for “connubial happiness” (Rossi-Wilcox 23).

That dictum appears in the introduction, almost certainly written by Dickens, to the menu book What Shall We Have For Dinner? by Lady Maria Clutterbuck, published by Bradbury and Evans in October 1851 and reprinted, along with a compendious exploration of its contents and context, by Susan Rossi-Wilcox in Dinner With Dickens. Lady Clutterbuck was a character played by Catherine in Used Up, an amateur theatrical produced by Dickens at Rockingham Castle in January 1851. The choice of nom de plume contains a sad and prophetic irony: Catherine’s role was as the woman rejected in the farce by Dickens’s character, Sir Charles Coldstream. Although it was several years later before the Dickenses’ marriage broke up, the book was put together at a difficult period in their lives, perhaps, Susan Rossi-Wilcox suggests (108), in hope of solving immediate financial concerns. In March Catherine was undergoing treatment in Malvern for post-natal illness; at the end of that month Dickens’s father died, followed two weeks later by the death of their infant daughter Dora.

The menu book, one of a great many self-help manuals of the era, was an undoubted success, revised for a new edition in 1852 and for another, enlarged edition in 1854, and re-issued several more times up to 1860. Its bibliography is frustratingly inconclusive, because surviving copies are rare. Rossi-Wilcox has traced “only five extant originals and two copies of any of the originals” after world-wide search (82). Its authorship is also problematic. Although the book is attributed solely to Catherine, she was seen discussing the contents in “serious consultation” with her husband by one of Mark Lemon’s children, who claimed that Dickens “had a finger in the pie” (Peek 15). Rossi-Wilcox is skeptical–Betty Lemon was only nine years old at the time–but Dickens was notorious for dominating every activity he entered into, and it seems highly unlikely that he would have stood aside from a project dealing with a subject so dear to his heart–and stomach.

Targeted at a middle-class audience roughly the same as that which read Household Words, What Shall We Have For Dinner? consists primarily of menus, with recipes for only a small number of dishes. The Dickenses entertained often, and a number of menus are designed for parties of ten to twenty, but the majority are for small family meals. As Rossi-Wilcox explains, the menus are practical, with a large portion based on ingredients available throughout the year, and organized from 1852 to reflect seasonal availability of foods. Victorian cooking was “hugely time-consuming” (Napier 13), and the Dickens menus are carefully planned to balance preparation of a combination of dishes. Later editions of the book are responsive to technical advances, as transport transformed the availability of products and kitchen ranges created new options for baking. Although French influence is evident in later editions, meals are distinctively British and informal, with strong Scottish flavoring, a reflection of Catherine’s origins. Like Household Words articles, the book is vigorously polemical, encouraging a taste for nourishing meals using inexpensive ingredients, striving to overcome national resistance to fish, and generally concerned “to improve the standard of British cooking” (78).

As Rossi-Wilcox recognizes, attitudes to food have wide social, economic, regional, cultural and idiosyncratic implications. In addition to statistical analyses of the menus, detailed discussion of ingredients, and thoughtful consideration of methods of preparation, she examines Catherine’s character, heritage, and her role as a Victorian housewife.

She considers the impact of their travels on the Dickenses’ taste in food, the management of the household’s staff of servants, and the political function of a book on food. Throughout, she adduces evidence for a judicious reassessment of the Dickenses’ marriage. Dinner for Dickens is a thorough, wide-ranging and informative study, a welcome addition to our shelves. With far more justice than Squeers, when he contemplated the watered down milk he diluted for his new pupils, one can truly say of Dinner With Dickens, “Here’s richness!” (Nicholas Nickleby, ch. 5).