Description

PPC 66 (May 2001)

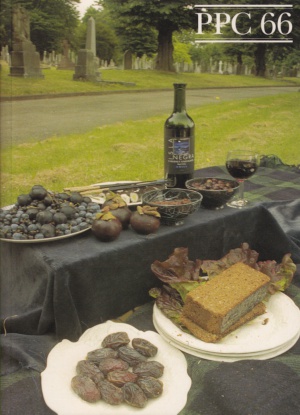

A picnic in the Victorian manner laid out in a London cemetery

ContentsBuy an individual article as a PDF

|

Notes and Queries

EGGS MARCONI from Barbara Santich

Has anyone ever eaten, or heard of, eggs marconi? It was served for breakfast in Melbourne in the 1930s or thereabouts, in the novel My Brother Jack (1964) by George Johnston. My research in Australian sources came to a dead end. My address is: 13 King Street, Brighton SA 5048, Australia: email Barbara Santich <barbaras@camtech.net.au>

MORE ON ARGON OIL from Gert von Paczensky

The stones do not all need to pass through the goat’s digestive system (see N&Q from Andrew Dalby in PPC 65). The women of the Tissaliwine Cooperative get a lot of them directly by shaking the tree’s branches, letting the ripe fruits dry, and then peeling them and cracking them to get the kernels. It takes about 30 kg of fruit to obtain one litre of oil. One tree produces only two to three litres. The harvests are decreasing due to overgrazing by the goats. The region of the argon trees was made a UNESCO biosphere reserve in 1998. In Morocco, one hears that the ‘passage through the goats’ produces a lesser quality oil. In Germany, argon oil is imported by a specialist in Munich. We pay DM29.50 per 35 dl. bottle, which seems reasonable in the light of its high quality. (By way of comparison, French pistachio oil is DM30 for a quarter of a litre.) I have heard of an importer in Paris who charges far higher prices than we pay in Munich, but I am also told he is no longer in business. Anyone interested may contact the German importer: Franz Wittmann, Hedwig-Dransfeld-Alle 20, D-80637 Munich. Gert von Paczensky <nc-vpaczege@netcologne.de>

THE TURKEY from Andrew Smith

For a possible book on the culinary history of the turkey (Meleagris gallopavo), I am looking for pre-1900 non-cookbook references to eating turkey. I also would appreciate any pre-1800 non-English-language turkey recipes or references. Andrew F. Smith, 135 Eastern Parkway, #11A, Brooklyn, NY 11238, USA: email <Asmith1946@AOL.com>

ROAST BEEF

We have had an enquiry from Ben Rogers, whose last book was a well-received biography of the philosopher A.J. Ayer, about the history of roast beef. He is writing a book, ‘Blood Relations; Beef, Bulls and English Patriots’, about the history of the bull dog, roast beef and John Bull. ‘It traces the history of our bovine national symbols and the rise of English/British identity. It concentrates on the eighteenth century – though ending, of course, with the Dangerous Dogs Act and BSE.’ He is having difficulty, he says, in identifying exactly when and why roast beef first became established as a national dish. Though so established by the early eighteenth century, it does not seem to have played an especially important part in the festive menu of earlier centuries. Foreign travellers always noted that the English ate a lot of meat, but they again did not begin to single out beef as a national dish until the 1700s. Suggestions please. Ben Rogers’ email is <brogers@freenetname.co.uk>

Book Reviews

Elizabeth David: Is There a Nutmeg in the House? Michael Joseph, 2000: ISBN 0-7181-4444- 59: 322 pp., b/w illus., bibliog., index, h/b, £20.00.

I am tempted to confect a little anthology of quotations from this last offering of works by E. David. These would give you the feel and scope of the book better than anything I might say. And they would tell you a lot about her personality. Some people have found her intellectually intolerant, unapproachable, dogmatic and overly stern. Although she can rant and rave as she rides her various hobby horses: garlic presses, stock cubes, onion salt ‘(something I can myself at all times do without)’ and the three Ps: pseuds, publishers and plagiarists, the overriding impression one gets is of scholarship, sensitivity, practicality and humour. The good humour vastly outstrips the occasional bad. So what is in this book? Identified on the dust jacket as a sequel to An Omelette and a Glass of Wine, it is a selection by Jill Norman, her long-time editor, of both previously published articles and unpublished items. The first six-and-a-half pages come from a Smallbone catalogue, dated Summer of 1989. Here are her childhood memories of the food she had in Sussex with her three sisters, and tit-bits about their way of life. Her reminiscences continue with the tale of her departure, aged 18, to join the Oxford Repertory Company, and her subsequent move to London. Then she jumps to her war years in Cairo, and then to post-war London. These recollections are mingled with her thoughts about food, cooking, cookery-books, and how they developed. Although these early years, (and the later ones), have been written about in much greater detail in two recent biographies (see PPC 64 for reviews), it is a delight to read what she has to say about herself. There is nothing like having people speak for themselves. The rest of the book contains her thoughts on a variety of food-related matters, including much practical advice and a substantial number of recipes. For some people these recipes, some never published before in any form, will be irresistible magnets. I observed at first hand the excitement with which one amateur cook fell upon a recipe for fish pie, handwritten in painstaking detail for her friend Lesley O’Malley. ‘Wow,’ he exclaimed, ‘this alone is worth the price of the book.’ I felt that I could spot the influence of her shop in her occasional references to the appropriate size and material of a pan to be used. She certainly helped me when I went to her shop many years ago wondering how to indulge my then three young daughters’ craving for pancakes, without my having to stand endlessly in front of the stove. Her response was to reach for a large cast-iron pan, on which with her finger she drew three imaginary circles showing how three smallish pools of batter could be arranged and cooked simultaneously; the operation to be repeated until either there was no more batter, or no more appetite. I have wondered afterwards whether she thought pancakes were an odd choice for children’s supper. She certainly didn’t show it, if she did. But perhaps her mind had darted to thoughts of Escoffier, about whom she wrote: ‘one has the impression that he did not ever entirely lose the taste for the village cooking of his very humble childhood, and that occasionally, bored with exquisite subtlety and the standards of perfection he had himself created, he had wistful hankerings for the primitive food of his childhood.’ As well as Escoffier, she writes thoughtfully about Stefani and his L’Arte di ben cucinare, and Robert May, La Varenne, Meg Dodds, A true Gentlewoman’s Delight and the Countess of Kent (which first appeared in PPC), and Redcliffe Salaman amongst others. Which reminds me, if you are tired of waiting for Alan Davidson’s long-heralded work on aphrodisiacs to appear in PPC, read what E. David wrote on Salaman and aphrodisiacs in The Tatler, reprinted in this book. Other subjects covered include Christmas eating, with recipes. Don’t be alarmed by her first words: ‘If I had my way – and I shan’t – my Christmas Day eating and drinking would consist of an omelette and cold ham and a nice bottle of wine at lunch time, and a smoked salmon sandwich with a glass of champagne on a tray in bed in the evening.’ She goes on to describe with sympathy and graphic detail the lot of the person who of necessity is cooking a large family Christmas dinner. Her observations ring too true, and I felt quite exhausted just by reading about it all. She does then suggest what and how to prepare more modestly a number of alternatives to be shared with a friend or two during the inescapable Christmas marathon. At this point, I am going to give up. Yes, there is much about bread, ice-cream and courgettes. The first two because of her own books on these subjects, and the last because although she thought she’d like to write a book about courgettes, she doubted that she’d get around to it. Some years ago, when I was sitting at my desk writing a book review for PPC, or to be more honest, when I had stopped writing it, because I felt stuck, the telephone bell rang. I pulled myself out of my mental thickets to hear E. David’s voice. She politely asked me how I was, and instead of replying ‘Very well, thank you,’ I burst out (as is my wont) by saying what was on my mind. To wit that I was stuck. Writer’s block. Call it what you will. Then I said, somewhat enviously: ‘I bet that doesn’t happen to you.’ There was a slight pause and then I heard the quiet voice saying something like, ‘Jane, you just have to persist.’ Well, I will persist for a little longer. I must tell you about one of the illustrations (page 119). This is the reproduction of a postcard showing a hirsute muscular man semi-reclining holding some food in his hand, an open white carton labelled ‘Quiche’ beside him. Large printed message reads: Real Men Eat Anything. The caption in the book says: ‘This made Elizabeth laugh, and she kept it for many years.’

J.M.D. Sri Owen: Noodles: The New Way: Quadrille, London, 2000: ISBN 1-902757-47-5: 144 pp., glossary, bibliography, colour photos, h/b, £14.99.

We had an energetic Christmas discussing why there were so many recipe books. The rate of eating out is on the increase, people spend less time in the kitchen, families rarely eat together as a group (say the surveys), most people work so hard they have no time for pickling pork, making horseradish sauce from their own thongs, baking bread, and so forth. Then we read an intelligent piece by Madeleine Bunting in The Guardian which drew attention to the fact that there were quite a lot of other things going on in these recipe books other than simple instructions for cooking. Then we started to do some very elementary statistics. There are 60 million people in the UK, say one million for every core adult year. Each adult will leave the parental home and set up independently and each adult will marry or cohabit at least once. Just those two events will provoke the gift of at least one cookery book. That makes a lot of books. Small wonder publishers fight for a place on the shelf. This by way of introduction to Sri Owen’s latest. If I were leaving home, I would want this as a really useful guide to tasty cooking. It’s short and to the point. Most of the recipes are clear and easy (and good, I am told by some who have tested them). One might wish for more information on noodles in history – but not if I were about to cook in my bedsit. It’s horses for courses.

Ruth Watson: The Really Helpful Cookbook: Ebury Press, 2000: ISBN 0-091-87798-9: 288 pp, colour photographs by William Lingwood, index, hardback, £20.00.

If I were getting married, I would be glad of this one. A straight line to bold suppers. But I am breathless, after only looking. Ruth Watson’s energy bounces; so too her prose. Her vivid images keep the reader smiling. Her recipes are in today’s kitchen lingua franca. Many first appeared in Sainsbury’s Magazine, pitched to a mindset and aimed at a shopping basket. They function smoothly. Ruth Watson is a restaurateur and loves eating out: it shows. It may give you stay-at-home blues. Her taste is for immediacy and occasional luxury (restaurants again). There are only a couple of stews and one savoury pie: and casseroles, what are casseroles? While most of the recipes need finishing à la minute, she is careful to describe how the preparation can be done hours, or even days, in advance so that dinner is not actually hell. Is it as helpful as the title implies? Quite possibly: there are delectable variations on well-worn themes (a vichyssoise with sweet potatoes, a cardamom trifle) and the novelties are fun.

Tamasin Day-Lewis: The Art of the Tart: Cassell and Co., London, 2000: ISBN 0-304-35439-2: 144 pp., colour photos, index, h/b, £16.99.

When you reach the age of discretion and feel all cooked out – are gasping for inspiration – this book is for you. I am phobic about pastry, it proved an antidote. The author’s optimistic tones are usually encouraging: the Day-Lewis kitchen is a place of constructive joy. The recipes are not impossible, the tastes direct and appealing. It is unfortunate that failing eyesight makes the text indecipherable: the type is a size more fitted to footnotes. The photographs (needless to add) are giant by contrast.

Shaun Hill: Cooking at the Merchant House. Conran Octopus, London, 2000: ISBN 1-84091- (131-X: 192 pp., colour photos, h/b, £20.

This is a gently attractive book. The recipes are likely to appeal to the comfortably middle-aged. They indulge in no fireworks, are appetizing and draw on several levels of experience, including the traditional, stomach-lining richness of classical, old-fashioned and bourgeois cooking. The commentary is disarming, nicely humorous, with plenty of short anecdote. Explanations as well as instructions abound, but do not overburden. The artwork is tiring but often successful. This is not one of those cooks that push you in a new direction (only to be dropped by the fashionable when another turns up), but he equips you with a fistful of things you want to try. Recommended. The star of the season.

Nigella Lawson: How to be a Domestic Goddess: Baking and the art of comfort cooking: Chatto and Windus, London, 2000: ISBN 0-701-16888-9: 374 pp., bibliography, index, colour photos, h/b, £25.

Few people have excited so much hot air as the author. Her charms irresistible, her brain impressive, her capacities infinite. Envy, jealousy, irritation, adoration and respect jostle in a single breast. That emotions are so extreme and contradictory is due mainly to the fear we are being had. The public manner, knowing aplomb and come-hither languor perhaps masking natural diffidence: is this adopted or the real face of the author? Is the whole thing a tease? Are the irritating asides an exercise in irony? How many of her vast audience appreciate the irony anyway? The title of this book is a case in point. Was it smart, or purposely meant to mislead? What we have is an intelligent collection of recipes for cakes and similar items dolled up with the usual wastefulness of pulp glossy publishing – a whole double-spread on vanilla sugar? There are quite a few American-inspired ideas (which may result in over-sweetness, but she does say ‘comfort’) and two of the cakes I made were exciting in their texture. A novice at cakes, pressing on as she advised, I was impressed by the result though terrified by the process. But the book is high on mood statement, low on information. It’s most attractive for its allusions: Ms Lawson is well-read and gets top marks for recommending Laurie Colwin among other authors. Nonetheless, I retreated to Geraldene Holt with relief. Now there is a domestic goddess.

Marguerite Patten: Spam – The Cookbook. Hamlyn, London, 2000: ISBN 0-600-60111-0: 64 “pp, colour throughout, h/b, £6.99.

A great subject, here treated by the one author most fitted to the task, her career having largely matched that of Spam. Quite apart from the recipes, which of course include an authoritative version of the world-famous Spam Fritters, there is an abundance of historical and anecdotal material, all highly evocative for those who can recall the period covering the Second World War and its aftermath. Indeed, there are three good reasons for buying the book. One is the light which it sheds on the genesis and uses of what has been a really important food resource for more than half a century. The second is for the recipes; gourmets may shrink from these, abut for lovers of plebeian food like myself they are a gold mine of a kind we do not often find. Thirdly, the book is lots of fun, a great read. A.E.D.

S. Douglas Olson and Alexander Sens: Archestratos of Gela: Greek Culture and Cuisine in the Fourth Century BCE: OUP, Oxford, 2000: ISBN 0-19-924008-6: 262 pp., indices, h/b, £48.

The Prospect Books edition was less costly. It was also shorter and lacked the visible underpinning of academic reference and the original Greek. The degree to which you will be the wiser for reading this version – if your interest is food and cookery – is not clear, but you will be the better read. So far as it is a book of commentary and elucidation, it seems model. Others’ opinions are weighed or disputed with courtesy, possible alleys of further investigation are signposted punctiliously, the prose is clear, a theoretical superstructure never obtrudes. As Athenaeus is the next Big Thing (and all of Archestratos was quoted by Athenaeus), the book should be obtained, though the price is more suited to the budget of a library than an amateur.

David Braund and John Wilkins, editors: Athenaeus and his World: Reading Greek Culture in the Roman Empire: University of Exeter Press, Exeter, 2000: ISBN 0-85989-661-7: 625 pp., foreword by Glen Bowersock, references, bibliography, indices, b/w illus., h/b, £45.

From the team that brought you Food in Antiquity, and in matching format. Athenaeus has everything: lots of food, buckets of otherwise unknown texts, material on dining customs in late antiquity, and a considerable body of material on sex. So far, he has figured as an item in myriad footnotes or as seven volumes of Loeb parallel text. Footnotes atomize him, he never exists in the round. The Loeb text is a very hard slog. This volume should go some way towards a broader understanding. As a product of a two-day conference, it impresses: the delegates must have been kept awake for more hours than usual. There are 41 papers divided into seven sections which cover the text and its transmission, its overall structure, Athenaeus’ intellectual cosmos, his representation of certain key authors, the symposium and what it meant, and Athenaeus’ comments on various aspects of life and dining customs. Finally, the two editors give us their view of his two other known works, a history of the kings of Syria and a commentary on the Fishes of Archippus. If one paper might be singled out, if could be John Wilkins’ on the structure of the work as a whole, for this book is about Athenaeus, not about the various texts he preserved for posterity.

Mark Grant: Galen on Food and Diet: Routledge, London, 2000: 0-415-23233-3: 224 pp., glossary, bibliography, index, p/b, £15.99.

Galen is another Ancient who pops up in footnotes but rarely anything more. He is a name, a theory, a useful reference, but who has actually read him? Now’s your chance. Mark Grant, who brought you Oribasius (another old medic) and Anthimus (via Prospect Books), has laboured hard to translate these texts into English for the first time. He has drawn on half a dozen treatises, the longest and most important being On the Powers of Foods. Others include a statement on humours (probably not by Galen), on the black bile, on the causes of disease, on barley soup and on bad temperament. He has written a brief but useful introduction, for the novice, and has provided plenty of notes. Galen thinks basil injurious and difficult to digest, and he thinks that the common habit of chefs of using ‘unsuitable seasonings in large quantities is such as to cause dyspepsia’. He had already twigged that refined bread was a food with little nourishment. No slouch Galen, and this translation makes him readable. His catalogue of foods is wide-ranging and informative. Good stuff.

H. T. Huang: Joseph Needham Science & Civilisation in China, Volume 6 Biology and Biological Technology; Part V: Fermentations and Food Science: Cambridge University Press, Cambridge, 2000: ISBN 521 65270 7: 741 pp, b/w illustrations and photographs, 3 (extensive) bibliographies, general index, Romanization conversion tables, h/b, £95.00 (US$ 150.00).

The monumental work of which this new part has now been published has borne and will always bear the name of Joseph Needham who wrote the earliest volumes and supervised work at the Needham Research Institute on others. Although, as in the present instance, other scholars have been responsible for the most recent volumes, the entire work remains harmonious in scope and style and standards of scholarship. Given the enormous importance of fermented foods in the cuisines of China, and the size of China’s population, it seems reasonable to hazard the statement that this 740-page book will, for the purposes of world food history, be the most important book of the decade. Everyone will find their own favourite chapters and sections. I have been reading with fascination the long passages on ‘fermented soy beans, soy paste and soy sauce’, replete with quotations from early sources and explanations of the scientific factors involved in the fermentations of these important items. And, having a particular interest in seafood of South East Asia and the uses to which fish are put in that region, I have been studying with especial care the deeply researched sections on fermented products such as fish paste and fish sauce, including for purposes of comparison a passage on fermented fish sauce in ancient Greece and Rome. In the light of what Huang has written, I will hasten to make some amendments and additions in books of my own. Had I ever wondered why fish sauce is not mentioned at all in the Chinese culinary classics of the 18th and 19th centuries, I would now know the probable explanation; and I now have important references to papers of which I had been unaware on fermented fish and shrimp products in Thailand, and on the 31 types of such products in Korea. No doubt people with other special interests will find corresponding revelations in other parts of the book, and will share my admiration of the lucid style in which the whole work is composed, and of the gifts of analysis and synthesis displayed by the author. A colleague with a particular interest in tea has already been learning a great deal from the chapter on ‘Tea Processing and Utilisation’, in which historical and scientific aspects are happily married. The illustrations are well chosen, for instance one showing inoculated cooked rice being dispersed on mats and trays at the end of the preparation of ‘red ferment’, hung chhü. This has an application in cookery as well as in making ‘wine’. The great poet and gastronome of the Sung dynasty, Su Tung-Pho (c.1036- 1101) wrote when he was in South China that he had been looking for local products for an old friend and had ‘sent him post haste’ two specialities, ‘cured mash’ and ‘red ferment’. I would ago so far as to say that this book is essential for any library of food history books. Its price may look high, but as soon as one realizes what a wealth of information lies between the covers, it will correctly be perceived as a real bargain.

A.E.D. Richard Hosking: At the Japanese Table: OUP, Hong Kong, 2000: ISBN 0-19-590980-1: 70 pp., index, colour photos, h/b, HK$85.

Multum-in-Parvo may have been the name of the high-kicking chestnut by which that spiv of the hunting field Soapey Sponge hoped to make his fortune, or at least a tidy sum, also it describes perfectly Richard Hosking’s new book. Taken with his Dictionary of Japanese Food, it makes the essential introduction to those who either fear the process of eating in Japan, wish to know more, or want to understand why things we view as slimy are valued by them as slippery. T.C. Lai’s At the Chinese Table is in the same series – another masterwork in miniature. It is to be regretted that the book, published by the Hong Kong office of OUP, seems not to be available to the English trade. Amazon calls.

Maria Dembinska, revised and adapted by William Woys Weaver: Food and Drink in Medieval Poland: Rediscovering a cuisine of the past: University of Pennsylvania Press, Pennsylvania, 1999: ISBN 0-8122-3224-0: 227 pp., bibliography, index, b/w illus, h/b, $29.95.

First the price: not excessive. Then the book: generous, creative American typography (often much more pleasing, when not burdened by quirks, than English academic presses), and enticing marginal illustrations. The original author we learned about from William Weaver’s piece in our last issue. The present author, Weaver himself, we know from his manifold ventures in food history, whether American or European. This book is Dembinska’s original research, presented as a thesis in 1963, considerably recast for a modern American audience. Weaver has also incorporated some material from Dembinska’s other work on medieval milling. And he has composed single-handed the thirty-plus recipes reconstructing the cookery of Poland in the Middle Ages. It is altogether impressive, readable and informative. That last epithet is the most problematic. Polish history is vexed by a lack of written sources – virtually nil for the early medieval period. Political onslaughts had their effect on documentary survival. Dembinska was fortunate in having the accounts of the royal household for the Jagiellon dynasty of the late Middle Ages, these form the kernel of the research effort, but she had to draw on many other avenues of investigation, ethnography or archaeology, or documents and printed books relating to periods other than the one at hand. This sometimes casts a pall of speculation over conclusions: ‘would have’ or ‘could have’ being mobilized to bring in parallel evidence. It also encourages an elastic view of time: something good for the seventeenth century may not have obtained in the thirteenth: a medieval year could be (though often was not) as eventful as a year today. Reservations such as these aside (and another might revolve around the dangers of giving too much credit to mythic individuals and their influence on the history of something as nebulous and intangible as taste and fashion), the book is a remarkable effort of reconstruction from intractable evidence. One of the big messages she promotes is that food consumption in medieval society followed economic laws, not those of status or social class. You ate what you could pay for (or what your employer could afford), irrespective of your nobility, position in the church or political influence. Another big message relates to Polish national identity and its culinary expression. A distinctive Polish cuisine came about with the melding of court habits and mass patterns of consumption. The court was open to foreign influence: Byzantine and Italian (the operations of these are of great interest), Russian (later on), Czech or Bohemian, as well as French or Cypriot and Mediterranean (the Angevin dynasty contributed its own king of Poland). The masses had their particular relationship with the products of the soil: turnips, millet, onions, parsley, and a number of what we now call wild plants (Good King Henry, bear’s paw, skirrets, sweet flag, alexanders, goutweed). Dembinska describes well the grain cookery of these farmers. One feels that the arrival of maize from the New World must have been the most providential relief from the deadening embrace of millet for millions of people (even if you hate polenta as much as I do). There is too much in this book to even start to give proper credit (though I would also wonder whether she was right in saying that the old name for vodka, deriving from the Polish ‘to burn’, hence ‘something that burns in the throat’: surely this meant the same as ‘brandy’, i.e. ‘burnt water’ because distilled over fire). And I have not even begun to cook the recipes which seem the most thoughtful and thorough attempts at reconstruction that I have seen for many years.

Peter Brears: The Compleat Housekeeper: A household in Queen Anne times: Wakefield Historical Publications, Wakefield, 2000: ISBN 0-901869-41-4: 136 pp., index, b/w illus, h/b, £18.

Peter Brears was lucky in 1992. He bought a volume of manuscript household accounts at auction only to find that they were for Kildwick Hall between Keighley and Skipton in Yorkshire, not a million miles from where he lives. It was a complete record of household expenditure for the family (comfortably off, but not stupidly rich: a lawyer and magistrate) during the years 1700-1716. This book is the result of close study. The author has tied the document to others in the family archive now in the Record Office in Bradford, he has illustrated it with his inimitable drawings, he has tipped in an infinity of local tit-bits that only he can know (after a career in museums, a lifetime of observing and recording domestic life) and the consequence: a thoroughly enjoyable canter through what might be an intractable crawl – it’s not just knowing what the words mean, it’s deciphering the spelling. After a good book of letters, or a densely written diary, household accounts come a strong third for enjoyment, provoking the imagination and consoling curiosity. This volume is excellent. There is something on every department of the house, plus hygiene, clothing, sport and gardening.

Timothy Morton: The Poetics of Spice: Romantic Consumerism and the Exotic: CUP, Cambridge, 2000: ISBN 0-521-77146-3: 282 pp., bibliography, index, b/w illus., h/b, £37.50.

This is a difficult book. It is modern literary criticism. It makes me feel old, want to go back to school, perhaps be born once more. I understand little of its vocabulary, syntax or terms of reference. It seems to be discussing the way in which spices were conceived (including sugar, but not chocolate, coffee or opium) by poets of the long eighteenth century – this includes Milton and William King (The Art of Cookery) as well as a poem by Eliza Acton, so it is an elastic Romanticism. Keats is at the climax of the discussion. The blurb helps: he ‘demonstrates how the emerging consumer culture was characterised by an ornate, figuratively rich mode of representation which he describes as “the poetics of spice”. This is the focal point for a probing analysis that addresses a host of related themes – exoticism, colonialism, the slave trade, race and gender issues, and, above all, capitalism.’ Spices are the prism through which he views his poetic world: every time they get a mention, he seems to have something to say, often not very connected with the last poem he dissected. Timothy Morton has also done this with food and Percy Shelley, a book I have yet to encounter. Much theory seems to come from Derrida and the Lacanian post-Marxist philosopher Slavoj Zizek. Although the book plays with the history of food, his readings are selective. Much of his historical scaffolding comes from syntheses (Mintz, Braudel, Montanari, Camporesi and Schivelbusch) rather than first-hand research, and his cookery books include Rabisha, Robert May and Richard Warner (who is important to one of his themes, that reference to spices was a form of archaism), but not Glasse, Bradley or other Anglo-French eighteenth-century texts. Nor does he take in Mennell or any modern English wor