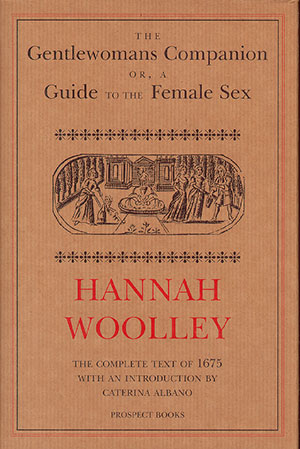

Description

Hannah Woolley

Edited by:

Caterina Albano

| Aphra Behn is usually described as England’s first professional woman writer, but her contemporary Hannah Woolley (Wooley or Wolley) ran her close, though recipes not bodice-rippers were her speciality (mixed with some judicious teaching, housekeeping and medical marketing). It seems amazing, therefore, that apart from a slight compendium, nothing of hers is available today – when women’s studies have so strong a following. Her output is confusing and disputed, even the portrait in this second edition of her book is not of her but one Sarah Gilly, but all is made clearer by the long introduction by Caterina Albano, who has studied women’s domestic literature for this period, and who urged us to produce this new, unabridged setting of the book (it is not a facsimile). The Companion is a conduct- as well as cookery-book (the recipes are mainly derived from her earlier works). It also contains an autobiography of the author. In truth it is a rank, but captivating, miscellany, including recipes, medical prescriptions, advice to servants and governesses, hints on upbringing, cosmetics and education, rules of social comportment and conduct, instructions and model letters for correspondence (mainly for young ladies), and ‘Pleasant Discourses and Witty Dialogues’ between gentlemen and ladies. Great bedtime reading. The editor puts it all in long perspective. |

Review by Lucy Lethbridge in The Tablet

Review by Lucy Lethbridge in The Tablet

It was one of the ironies of history that many of the women who most vociferously advocated the traditional virtues of the stay-at-home housewife were themselves independent career women living by their wits outside the domestic sphere. Hannah Woolley was said to be the first woman ever to earn her living by writing, but in her book The Gentlewoman’s Companion (subtitled A Guide to the Female Sex) she laid down the law when it came to achieving feminine perfection: those who were not modest, almost completely silent and did not know about preserving fruit and curing constipation simply stood no chance of getting a husband and would be held in “meer pity” by the rest of society, particularly other women. It was this pity, says Woolley, which drove her to pen this self-help manual in 1673 for the woman who wishes to become a lady, to learn “the laudable sciences which adorn a compleat gentlewoman”.

It was tremendously hard work: you secured a husband by keeping your mouth closed while eating, and learning French, and when you were married you had to remember details such as not to “suck your knuckles” while carving fowl. And frivolities were out: patches, powders, even farthingales.

The seventeenth-century compleat gentlewoman toiled away acquiring skills which she would then pretend she didn’t have, or had at least effortlessly acquired, in the interests of preserving the modest restraint which was her hallmark. (Though Woolley breaks her own rule by including a long list of her accomplishments: still, I suppose she had to keep an eye on her career.)

Nothing is left to spontaneity – least of all courtship. A quick flick through The Gentlewoman’s Companion gives you a useful response to a keen suitor: “Sir, I have absolutely render’d myself up to the disposal of my dear parents, consult them: if you prevail on their consent, you shall not doubt the conquest of my affection.”

But what makes this book so fascinating is the sense of sheer hard work involved in running a seventeenth-century household, the vivid details it gives of daily life. It’s hard to imagine that a woman who kept her eyes always downcast would have been able to oversee cheese making, the preparation of sometimes extraordinarily complicated foods, preserving for the winter, slaughtering animals. Woolley includes a guide to what food is seasonal: green geese in April, mince pies in January, pigeon pie in August. There is a long section on remedies for various ailments. Demure she may be, but the gentlewoman is not squeamish and a good thing too when the best way to cure corns was to rub live black snails on them.

This wonderful new edition of the Companion, beautifully produced, comes with an excellent introduction by Caterina Albano and an equally excellent glossary.