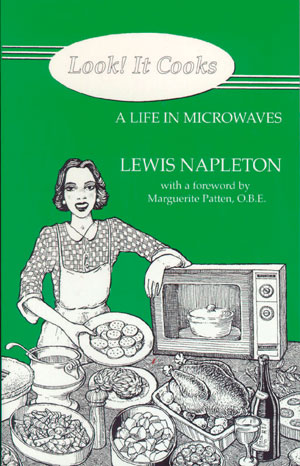

Description

Lewis Napleton

Look! It Cooks

A Life in Microwaves

| (with a foreword by Marguerite Patten, O.B.E.)

The microwave oven is the most important technical innovation in the kitchen of the twentieth century. Most other technical developments had been pioneered in the Victorian age or before, even if their consequences were not fully absorbed until the modern era. The microwave, however, was wholly new, a chance spin-off of the development of radar in the Second World War – the first ovens were called ‘Radaranges’. The first commercial applications and patents were based in the U.S.A. but there were parallel developments in Britain and Europe, the most important of which centred on the firms of J. Lyons & Co., and the Dutch firm of Philips. Lewis Napleton, a fresh-faced boy just out of the RAF, joined the food manufacturing and tea-shop-owning firm of J. Lyons in the early ’50s. He was soon closely involved in microwave projects during his pupillage there. He went on to devote the rest of his professional life to the promotion and sale of microwave ovens by Lyons, Philips, and the American firm of Litton. This book is a memoir of his part in this pioneering episode. When the history of modern food and cookery comes to be written, it will be an important primary source for tracing the patterns of promotion and up-take of this device – particularly the way in which it was first linked to commercial foodservice exploitation before its entry into the domestic market. The microwave is now the biggest-selling item in domestic white goods. This little book has many amusing anecdotes, including an early sighting of Baroness Thatcher when a colleague at Lyons, and is plentifully illustrated with contemporary photographs of microwaves in their period setting. |

Review in Foodservice Equipment Reports (10/02)

contents

Prologue – Can it cook?

Chapter One – Prove it!

Chapter Two – Can we sell it?

Chapter Three – Of course we can!

Chapter Four – Let’s try again!

Chapter Five – Now they all want it!

Epilogue – Seriously, though

Prologue – Can it cook?

When I first heard about microwave cookery, I had no idea that it would eventually have such an impact on so many people’s lifestyles and my own career. It was 1950, shortly after microwave ovens had been launched in America, and I was doing my National Service in the Royal Air Force. Wide-eyed, eighteen-year-old fellow conscripts and I listened in awe as a lecturer dramatically pointed out that radio sets and television sets were now to be joined by ‘radar sets’ – or microwave sets. ‘At the heart of each microwave set,’ he said, ‘just like the cathode ray tube in a television set, there is a valve called the magnetron. Americans call it a “tube”. It generates electromagnetic waves, and these waves may be used to create heat, as if you were cooking in an oven.’ This cooking potential had been discovered during World War II when, under a cloak of secrecy at Birmingham in 1941, two British scientists called Randall and Boot carried out experiments with radar, then regarded as the country’s most valuable invention.

The war effort was imposing so many demands and strains on Britain’s resources that outside help was desperately needed for the production of radar equipment. It was sought and subsequently obtained from America, then neutral but Britain’s nearest potential ally. The name of the American company selected for sharing the secret of this technology and becoming involved in the covert development and production of radar was Raytheon. Its management soon realized the commercial opportunities presented by this new form of heating and immediately took out patents for its use in the United States. As a result, in 1949, it was Raytheon which launched a small number of large, heavy, microwave appliances on the American foodservice market.

My own involvement with microwave ovens began in 1954, when I was working for the British firm of J. Lyons. Before that, it had been intended that after leaving school I would study at a catering college, then complete my training in hotels abroad. But the best laid plans go astray. Like other students at that time, I went straight from school into National Service and military training with the Royal Air Force. Of course, we all wanted to spend the next two years as air-crew, but for one reason or another most of us failed the stringent tests and had to make other choices. Of the remaining options open to us, the next most popular was to be selected for training on modern equipment such as radar. To become associated with this new high-tech. phenomenon was prestigious. Its appeal was heightened by its mystery and the myths which surrounded its discovery. These included stories of how radar or short radio waves could create remarkable heating effects. One mythical tale revolved around sentries who guarded radar stations being accustomed to witness flying ducks colliding with their radar masts, then falling to the ground, nicely cooked. Another was of aircraft pilots who used their radar equipment to warm up snacks, or dry out damp gloves after bombing raids. It all seemed irrelevant and inconsequential at the time, but started to make sense later. The first microwave ovens were indeed called ‘Radaranges’ and for some years to come, American chefs about to cook or heat food in the microwave oven would say, ‘Stick it in the radar.’

National Service over, I went on to a catering college, completed my course, and applied for a job interview with the country’s best-known caterer, J. Lyons & Co. At its vast Cadby Hall headquarters in West Kensington, ten thousand people worked in a number of bakery, food and ice-cream factories. Here was the administrative hub of an empire that encompassed another thirty thousand employees at their Teashops, Corner Houses, hotels, depots and other factories throughout the country, as well as being a vital manufacturing centre in its own right. My ambition was to get one of two advertised trainee positions in Cadby Hall kitchens, where frozen, chilled and fresh foods were centrally prepared for Lyons own foodservice establishments, other caterers and the retail market.

The interview day came. Arriving from Halifax, I walked down Kensington High Street, past Olympia, then towards Cadby Hall, looming through the swirling smog like a huge, foreboding fortress. At the gates was a commissionaire: one of those resplendent old coves with mutton-chop whiskers. He asserted his authority in that élitist, condescending way so many of his generation reserved for momentarily inarticulate victims seeking their assistance. Grandly, he waved me towards Personnel. There, outside the interviewer’s office, sat four of my short-listed adversaries. Soon, each of us was cautiously conversing, sizing the others up, contemplating our chances.

Last in line, it came my turn to be interviewed. By now, self-esteem had taken a bit of nose dive. The smog (a real old London pea-soup) had deposited soot on my crisp, white, starched collar. During the long, tense wait, I had slipped out to the toilet, found the soot and made a disastrous attempt to wash it off, leaving an even worse smudge. The smog had also saturated the front of my hair. Despite my frantic attempts to damp it down with a comb, it now spiked up in dreadful disarray. To add to my misery, I had discovered that my adversaries were articulate and appealing, and probably going to be much better at presenting themselves than I was. In our competitive, pre-interview chit-chat they had already scored points at my expense.

Vacillating between courage and cowardice, I marched uncertainly into the office. There, the bespectacled, grey haired old gent who sat behind a huge desk, cast me one of those dismissive, half-interested looks. It was almost as if he were challenging me to surprise him. For a mad moment, my adrenalin flowed and I was tempted to say something wild and outrageous. Then courage deserted me, sanity returned and I abandoned the risk. So we sat down to the ritual. He meandered through the motions of putting me at my ease by asking a few simple questions, and talking about the company’s needs and wants. Then, these formalities swept aside, he started his cryptic interrogation. My confidence waned. I had not anticipated half of the questions he asked, and even to those that I had, my inane, somewhat feeble replies hardly seemed to reflect the stuff of which potential managers are made.

I lost my concentration. My mind wandered. I started noticing little things, such as his nicotine stained fingers, the scribbles on his blotting pad and the way the daylight behind him danced upon his spectacles. I barely saw his eyes, and was in no position to sense his reactions to my half-witted responses. It seemed obvious that we were playing out a futile charade. I wondered how long this could go on: whether there would be sufficient time for me to catch one of the earlier trains back to Halifax and whether it would have a dining-car.

Then it happened. His attitude changed. He leant forward in his chair. Now I could see his eyes, which were burning bright with interest. Within a trice, our interview was back on course. In an eager, incredulous and high pitched voice, he ventured, ‘I see here on your application form that you have played for Halifax?’

At first, the suddenness of his statement took me by surprise. Then, swiftly making a somewhat devious effort to exploit his new-found interest while showing a modicum of modesty, I replied, ‘Well, yes, just on and off, for the last two seasons.’

It worked. His disposition switched from that of benign, bored inquisitor to beaming benefactor. If you believed in fairy tales, it was as if I had waved a magic wand. He talked on. There was no need to answer his questions now. I could hardly slip a word in edgeways as he went into ecstasies describing the sports and social facilities at Lyons. My confidence flowed back. Then suddenly, he emerged from his euphoria, and dismissed me with a curt but friendly, ‘Look, it’s getting late. You need to catch your train home. You will hear from me next week.’

I travelled home, painfully aware that I had been swept along by events outside my control and beyond my comprehension. I was totally confused as to whether it had gone well or otherwise. As it happened, I need not have worried. In the following week, I received a letter and was offered the job. I gave up trying to reason, and decided to grasp the opportunity.

A few weeks later, after plodding the streets to prospect accommodation in West London, I had found and settled into a house in Shepherds Bush. It was managed by two elderly sisters and was twenty-five minutes’ walk from Cadby Hall. The next day, I strode past a line of early-morning day-workers queuing outside the offices on my way to attend Lyons’ customary induction programme. I listened to talks, watched films, received my kitchen gear and was introduced to the superintendent of my first training department – the pudding kitchen. It was just like going back into National Service.

Next morning, just after 6 am, I was clad in tall hat, whites and clogs, and beads of sweat ran down my forehead as I stirred a huge copper full of hot sauce in the dimly lit, steam-laden atmosphere of a basement kitchen. I began to wonder what kind of an idiot I had been; whether my enthusiasm for the job had exceeded my judgement. By the days’ end, I ached in every limb, and the walk to my new digs, so short and stimulating a few hours earlier, now resembled a marathon. It was but a foretaste of the training that was to follow over the next three and a half years.

During the week, I met two bakery trainees who had started about the same time as myself. One was a good rugby player, and it was he who helped solve my employment mystery. Our Personnel Manager was an avid rugby fan, totally dedicated to developing Lyons’ first team. So that was it! When I mentioned Halifax, he thought that I had played for its prestigious Rugby team instead of Halifax Town, the soccer team, which in those days was part of the Third Division North League. He must, I suppose, have realized his mistake at some time, but was probably too embarrassed to mention it. Of course, I never mentioned it, either.

It was 1954, and about five years after the first conveyorized industrial microwave heating equipment, such as the large, static box type microwave ovens and sandwich defrosters had been introduced and tried with little success in America. Now Lyons was going to be the first British company to have an opportunity to test them. This was an era when Lyons was not only in the forefront of food applications technology, with a unique knowledge of food regeneration systems, but had also just introduced Europe’s first major computer. It was called LEO, an acronym for Lyons Electronic Office. Besides forecasting and order-processing all of Lyons’ Teashop and Corner House requirements, LEO was also used to compute Lyons’ and other companies’ payrolls. Its design, operation and maintenance required considerable electronics expertise. This was mostly provided by a team of Cambridge graduates. With such a background in both food and electronics, and its enthusiasm for innovative improvization, it was hardly surprising that Lyons should be so interested in the potential of microwave heating.

Luckily for me, the opportunity to work with conveyorized and cabinet type microwave ovens occurred in my first year with the company. Thereafter, throughout my three-years’ training course, I was to be tagged ‘Mr Microwave’ and was made to work on every microwave project undertaken by Lyons. In consequence, my training programme was extended from three to three and a half years, but the knowledge I gained more than offset the extra time invested.

My initial training over, I progressed through several factory management positions but was always on call to work with others with whom I would evaluate different types of microwave appliances in all sorts of food production and service situations. This was a time when Lyons was in its heyday, bullish and bristling with personalities and clever, inventive people. Such was its interest in modern equipment systems that it eventually created a development department, staffed by myself and a small team of chefs and foodservice specialists.

Our purpose was to investigate new food product and service opportunities. As a result, we became involved in all sorts of projects, from the development of new frozen, chilled and ambient products to the evaluation and implementation of new service systems. One, for instance, involved an American called Larry Foster, with whom we carried out tests on refrigeration equipment. Today, Foster Refrigerator in King’s Lynn, Norfolk has a multi-million pound turnover. Another project involved the planning, setting up and initial management of Britain’s first food factory to make frozen entrées in boilable bags, eventually producing a million portions per month, and becoming the forerunner of many of today’s boilable bag products.

As we progressed, microwave heating projects took a higher and higher proportion of our time. There were so many potential food applications to investigate, from prime cookery (that is, cooking from scratch as opposed to reheating) to the development of specially packaged food products – not only in Lyons Corner Houses and Teashops but also for food retailers and every type of foodservice outlet. It was not long before microwave ovens became a priority in our work schedule, and eventually, a full time commitment. But I am jumping ahead. Let me start at the beginning, to describe what became a hair-raising and fun-filled journey.

Review in Foodservice Equipment Reports (Oct 2002)

In ‘Look! It Cooks’ – subtitled ‘A Life in Microwaves’ – the author Lewis Napleton really does a nice job creating a you-are-there history of the development of microwave ovens. Napleton, who was there, offers up a bit of time-travel experience that’s part techno-history, part autobiography, part classic marketing and part socio-cultural documentary. And all of it is delivered with a subtle – and sometimes not so subtle – British wit and style. For foodservice professionals, the particulars on the microwave (not to mention outlandish goings-on at the Hotelympia show) are entertaining and enlightening. For product developers and markets, ‘Look! It Cooks’ is a great case study of new-product launches, engineering vs. marketing and technology vs. applications.

The prologue plunks you squarely into 1950, with a young Napleton in the Royal Air Force, where he first learns of microwave ovens. The author then zooms past his completion of R.A.F. service and entry into catering college, and the story begins in earnest in ’54 as he applies for a kitchen trainee job at J. Lyons & Co., the famous U.K.-based food-manufacturing and multiunit catering concern.

The requisite historical facts are in place, of course. He nods briefly to the ’41 invention of radar by two British scientists and the coinciding discovery that radio waves could excite water molecules and hence cook. He notes, too, that the war effort required large-scale radar production, and it was American manufacturer Raytheon that was approved to share the technology and crank out radar sets. By ’49 Raytheon was into microwave ovens.

But it’s the eyewitness, human aspect of the story that’s most compelling. These are people with quirks and personalities, personal priorities and career conflicts. Napleton traces his own path through J. Lyons, where, because of his cooking training plus his engineering inclinations, fate sucks him inexorably into the development of the newfangled microwave oven as well as its pioneering sales and marketing. From there he moved on to Dutch conglomerate, Philips, and eventually to Litton.

There are many truly funny moments along the way. At one point he tells of the terror of spilling pudding on a very pernickety and meticulously tailored boss at J. Lyons. Later, as a new employee at Philips, he recalls the awkwardness and fear of being cornered into insulting a roomful of Philips engineers who obviously knew molecules but had no clue about cooking. Elsewhere in the book he recalls cockroaches interrupting client presentations, units exploding on tradeshow floors, the difficulty of installing 400-lb. units in the days before modern electronics, and much more.

Napleton’s examples of how leasing made all the difference in the early days, and how vending applications led to innovations such as programmed-time tokens, also will give you food for thought in modern-day adaptations.