Description

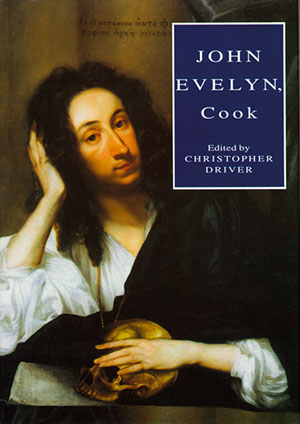

John Evelyn, Christopher Driver (ed.)

John Evelyn, Cook

| John Evelyn (1620-1706) was a virtuoso, scholar and man of letters of Restoration England. His diary is required reading, his architectural and environmental treatises were phrophetic, and his gardening was legendary.

Among his manuscripts, now in the British Library, is a volume of receipts or recipes: for the stillroom, the sickroom and the kitchen. Those of cookery are printed here; in an edition that includes a full glossary, index of ingredients and biographical introduction. (A superglossary is also available on this web site.) The recipes range wide over the repertoire of the seventeenth-century household; from liver puddings to excellent syllabubs. They include items picked up on his travels in Europe, as well as favourites given him by friends – such as that for gooseberry wine contributed by Sir Christopher Wren. The manuscript has an added attraction: it contains the recipes that Evelyn later printed in his book about salads, Acetaria. No other printed cookery book from this period can demonstrate this development of a recipe from first inception to the finished page. |

Review by Helen Peacocke in the Oxford Mail

Review by Frances Bissell in the Hampstead and Highgate Gazette

Review by Helen Peacocke in the Oxford Mail

Those who already own Prospect Books’ excellent facsimile copy of Acetaria – A Discourse of Sallets by the 17th-century diarist John Evelyn, will be aware of his uncommon interests in culinary matters.

It was Evelyn who suggested enriching salads by rubbing garlic around the dish as the Brahmins did.

Last year food writer and broadcaster Christopher Driver edited the new edition of Acetaria, and now he has edited the rest of Evelyn’s recipes.

This is a superb little book. Evelyn was a man who loved knowledge and spent many hours hoarding it. His manuscripts, which are now in the British Library, were stored in Christ Church Library for more than 40 years.

It was in the 1950s that Driver (then an undergraduate at Christ Church) first encountered a large volume bound in decorated calf and gilt, with Evelyn’s arms on the cover and his woodcut bookplate inside.

It was entitled Receipts Medicinal and contained prescriptions for sick cattle, also recipes for the still-room, formulas for preserves and perfumery and culinary recipes.

At the time Driver expressed surprise that no publisher or scholar had mined this rich hoard, and so in later years (with permission of the college) he painstakingly copied out the 343 recipes from this unwieldy folio.

The recipes range over the repertoire of the 17th-century household and contain many recipes given to Evelyn by his friends, including a recipe for gooseberry wine attributed to Sir Christopher Wren.

This fascinating collection includes instructions for ‘puffe-paste which requires the yeolkes of six eggs and the whites of four, some fine flowere, sweete butter in very thicke pieces as big as wallnuts which is rolled out seven tymes, every tyme putting in more butter.’

Among other things this splendid collection also contains recipes for an oatmeal pudding, cowslip wine and an excellent syllabub.

This book may not provide the recipes you need for your next dinner party, but it does offer a remarkable insight into the 17th-century kitchen and the mind of a remarkable scholar who was considered (among other things) an interpreter of changes of taste.

Review by Frances Bissell in the Hampstead and Highgate Gazette

I was reading John Evelyn, Cook when Christopher Driver’s death was announced. The transcription and editing of this important 17th century manuscript was the last major work to be undertaken by Driver, one of Britain’s foremost writers and thinkers about food.

His family and friends must surely derive some comfort knowing that he was able to see the finished publication.

John Evelyn was one of the great and good of his day. A founder member of the Royal Society, diarist, traveller, gardener and influential thinker, and writer on these and other subjects. Evelyn does not deserve to be overshadowed by his contemporary, Samuel Pepys.

This is the second in a series reprinting his manuscripts, which have now been bought by he British Museum.

They give a lively and engaging picture of comfortable 17th century life, and show us a man whose preoccupations were not much different to our own, including atmospheric pollution in London.

But this part of the oeuvre is Evelyn’s cookery notebook, recipes collected from his travels, his friends and, no doubt, from he inspiration provided by his own garden.

There is much in it that speaks to the present-day cook and, indeed, cookery writer. Recipe number 146 is for ‘a very good cake. Mrs Black[wood?]. If it had bin given right which upon triall does not answer.’ Ouch!

Recipes for preserves, puddings, cheesecakes, possets and especially salads could be tackled today relatively easily, and I have already started recipe number 50 ‘Orrenge leaves. Set or sow the seeds of orenges and lemmons, and when they first appeare Croppe them and put foure or 5 into any sallet, they render an admirable taste.’

Here is clear evidence, if any doubters remain, of strong English culinary traditions and practice.

Here are fruit fools, pickled walnuts, shrewsbury cakes, apple tart, damson cheese, elderberry wine, rice pudding, syllabub, collared beef, mince pies, and many more familiar dishes.

Here too are many that we no longer cook and that we might now, thanks to Christopher Driver, include once more in our repertoire.