Description

‘Wyvern’ (Colonel A.R. Kenney-Herbert)

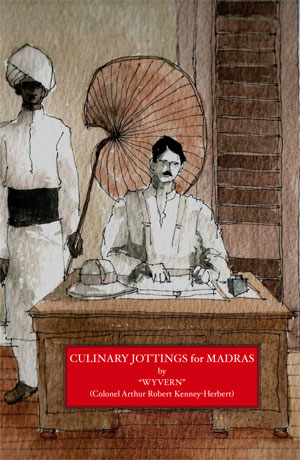

Culinary Jottings for Madras

‘Wyvern ’was a colonel in the Indian Army, long resident in Madras, who whiled away his spare time writing about cookery in the Madras Athenaeum and Daily News. The upshot of his interesting hobby was this book, which set out to instruct the memsahibs of the day in the best ways to cope with Indian kitchen staff and cooking arrangements and in how to produce decent English and French food with local ingredients and imported supplies. It was first published in Madras in 1878 and went through several editions in India. Our facsimile is of the 1885 edition. It is a fascinating hybrid, for it tells the modern reader a great deal about Anglo-Indian cookery and gives a matchless description of Victorian haute cuisine. There is possibly no better introduction to good cookery than this book. So talented a teacher was ‘Wyvern’ that eventually he came home to Britain and set up a cookery school in London. His subsequent books, most notably Commonsense Cookery, were also models of their type, though in many respects never improved on his first attempt published here.

The chapters cover every aspect of the kitchen, from the cook and his management, the store-room, and the batterie de cuisine, to all dishes suitable for dainty dining, as well as excellent chapters on ‘Our Curries’ ,‘Camp Cookery ’and ‘Our Kitchens in India’. There are extensive model menus for parties of six or eight people, or for ‘Little Home Dinners’. Elizabeth David once said of this book: ‘I should recommend anyone with a taste for Victorian gastronomic literature to snap him up… His recipes are so meticulous and clear, that the absolute beginner could follow them, yet at the same time he has much to teach the experienced cook.’

Leslie Forbes has contributed a bravura introduction. She has herself travelled widely in India and wrote an excellent book on Indian cookery as well as a highly regarded radio series on the topic. Leslie Forbes has worked in London as a writer, artist and broadcaster for over 20 years. She is the author of four award-winning travel books, including the worldwide bestseller A Table in Tuscany and the presenter of many celebrated BBC radio series, several based in Italy. Her first novel, Bombay Ice, published in 1998, was an international bestseller and her second, Fish, Blood &Bone (2000) was nominated for the Orange prize.

First published by Prospect as a facsimile in 1994; the present edition first published in 2007.

PDF of the preliminaries and the first pages of Leslie Forbes’s introduction to Culinary Jottings for Madras

Review by Vikram Doctor in The Economic Times (Bombay) (02/05/08)

Review and comment from Christopher Hirst in The Independent (08/03/08)

Review by Vikram Doctor in The Economic Times (Bombay) ( 2 May 2008)

I first came across Colonel Kenney-Herbert while reading Elizabeth David. This British writer who has near Goddess status in food writing was an admirer of the Colonel, praising his Culinary Jottings for Madras particularly in her study Spices, Salts and Aromatics in the English Kitchen. That was some recommendation and I was also intrigued because I had just moved to the city that was still to be called Chennai. Who was this culinary genius who had flourished in such apparently unpromising surroundings?

Madras at that time was hardly the Raj city of the Colonel, but vestiges still existed in grand old buildings, in Higginbotham’s booksellers which had published his Jottings, and the cavernous halls of the old Spencer’s department store which would have supplied him with the imported tinned food whose over-use he deplored, but which he was often forced to use in order to produce what he felt was an acceptable standard of dining. These were just vestiges, and I thought the Colonel’s book would bring them to life so I searched hard for it. I asked second-hand booksellers and checked old libraries, but no one had a copy. Finally, a few years back, I got one thanks to Mr. S.Muthiah, Madras’ historian, who had himself made a copy from a book found in a British library. Promising to return it soon, I fled to a photocopying shop and made my own copy from it.

It was worth the trouble. The Colonel’s Jottings, which he published under the name ‘Wyvern’ (which I’ll use for brevity) is wonderful for many reasons, of which nostalgia is just one. Its certainly interesting reading anecdotes from his career which spanned from 1859, just after the Rising, to 1892, near the apogee of the Raj, but the book was never meant to be a memoir. It really is, as he explained with full Victorian floridness: “A Treatise in Thirty Chapters on Reformed Cookery for Anglo-Indian Exiles Based Upon Modern English and Continental Principles with Thirty Menus For Little Dinners Worked Out in Detail.”

To deconstruct this imposing subtitle one has to understand the culinary history of the period Wyvern wrote in. Coming to India in 1859, as a young man he would have known many British residents from the East India company days when it was acceptable to adopt many Indian customs including eating mostly Indian food. Wyvern fondly recalls a “fine old servant of honest John Company” who would host ‘tiffin’ parties where he served “eight or nine varieties of curries with divers platters of freshly-made chutneys, grilled ham, preserved roes of fishes, &c.”

But Wyvern’s time in India saw the end to this world of Anglo-India (the phrase used to mean literally the British in India, and not the mixed race community that took on the name later) and the establishment of an Empire where British and Indians were rigidly divided. This was reinforced was by the insistence that the British live in a style identical (just grander) to what they would have lead back home. So curry might be acceptable for breakfast or lunch or a private meal at home, but for formal public purposes it had to be British. As Wyvern notes in his introduction, he no longer saw any use for a curry based cookbook for the “Anglo-Indian in England”; what was needed was to make food fit for “the Englishman in India.”

The problem was that what this meant wasn’t too clear since English food itself was undergoing profound change. The country based cooking of the past was being abandoned as England industrialised, and its new wealth drew foreign chefs like Francatelli and Soyer to London to set a new French influenced style. But there was a lot of confusion and poor execution, and this is what Wyvern wanted to correct. He clearly had plenty of experience of the new cooking, yet he didn’t go to the fashionable extreme either and denigrate all English cooking. He notes approvingly how a French waiter only coats salad leaves with the lightest vinaigrette dressing (“The thing to avoid is a sediment of dressing”), but also goes into the details of how to make a good English bread sauce or brown gravy.

Nor, despite his subtitle, does Wyvern disdain curries. He points out that because they are falling out of fashion people are forgetting how to make them properly, so have no idea of how good they can be. Naturally he’s well aware that all curries aren’t in the Northern style that others assumed was standard for all curries, and he emphasises the value of typically South Indian ingredients like tamarind and coconut milk. His appreciation for Indian vegetables is also quite unlike the British (or many Indians for that matter): “With cold cooked country vegetables, I have made capital salads; young brinjals, the mollay-keerai, bandecai, country beans, greens of all kinds and little pumpkins gathered very young, are all worthy of treatment in this way.” He even recommends snake-gourd, ‘podolong-cai’, cooked in brown gravy as “well worth trying when vegetables are as scarce as they always are in hot weather.”

That’s an interesting way to look at snake-gourd, a vegetable most people turn up their noses at, and it shows another reason to value Wyvern. The Jottings fall into an interesting category of books on how to make foreign food in India, written by foreign writers based over here (Tarla Dalal on Mexican food does not count), so there is both authenticity and practical applicability. The entertaining Italian cookbook Food Is Home by the Goa based chef Sarjano is one example, and then there’s The Landour Cook Book from American missionaries based in that hill station, a book on Vietnamese cooking by the Vietnamese wife of an erstwhile director of the Alliance Francaise in Chennai, and other such books by the wives of diplomats. Their great value is to show us how to look at available ingredients here differently, as Wyvern does with coconut flowers: “A very superior dish… The white stalks of the flower, if quite young, can be served exactly like asparagus. I.e.: – boiled, laid in a very hot dish, with plenty of butter melting over them…”

Parts of the Jottings, it is true, can make one squirm since Wyvern didn’t escape the British prejudices. A running theme in the book is to talk about ‘Ramasamy’, meaning the standard native cook, whose abilities he acknowledges, but whose many shortcomings are deplored especially in comparison to ‘Martha’, a standard plain English cook. Ramasamy’s shortcomings include lack of cleanliness, love of shortcuts like using tins and taste for dubious decorations like country parsley (coriander leaves). It easy to get annoyed by this, until one considers how often we’ve heard upper-class housewives in India say exactly the same thing about their cooks. Wyvern is also fair, and his real point about Ramasamy’s failings is that they are due to employers who don’t get involved with their kitchens, leaving the cook directionless, yet faulting him when problems inevitable rise.

Wyvern’s basic message is that we need to think intelligently and without prejudice about the food we eat. This is conveyed in a manner that is detailed without being boring, stern without being forbidding, and leavened with a bluff, military sense of humour and an unselfconscious appreciation of the joys of food. It’s not far from Elizabeth David’s own style, so one can see why she appreciated him. The good news now is that Culinary Jottings for Madras has been reprinted by Prospect Books, the specialist food book imprint set up by the late Alan Davidson. Tom Jaine, who has revised and extended Davidson’s magisterial Oxford Companion to Food, now runs Prospect and very kindly sent me a copy of the reprint (their second, after a first in 1994), which has an introduction by Leslie Forbes with details of Wyvern’s subsequent life.

This is a facsimile of the fifth edition for which Wyvern added on a fascinating essay on Indian kitchens, which for some reason was dropped for the seventh edition which is what I had earlier. Wyvern seems to have fiddled around quite a bit with his editions and given how interesting he always is, it would have been nice to have an appendix with all the major changes. But that’s a detail, compared to the joy of having him back in print at all. Sadly Prospect doesn’t have an Indian distributor so those who want the book will have to order directly from their website at www.prospectbooks.co.uk. I hope an Indian distributor will take up Wyvern’s book, which should never have vanished from our book and kitchen shelves.

Review and comment from Christopher Hirst in The Independent ( 8 Mar 2008)

The Weasel: A passage from India

Let’s apply the chilling exam phrase “compare and contrast” to two recently re-issued cookbooks, which I shall temporarily cloak in anonymity. Book A recommends that “the store cupboard can be stocked with treasures”, such as Heinz Tomato Frito and English Provender Very Lazy Caramelised Onions. Book B takes a similar tack, though with some reluctance: “There will be times and places when and where you will be obliged to fall back upon Messrs. Crosse and Blackwell and be thankful. Until those evil days come upon you, however, do not anticipate your penance.” Book A briskly tells us to “cook the linguine in 2.25 litres boiling salted water for 8-10 minutes”. Book B tackles the same process with metaphor and imagination: “An occasional bubble is what you want, with gentle motion, the water muttering to you, not jabbering and fussing, as it does when boiling.” Book A is currently No.1 in the Amazon UK sales ranking, while Book B is No. 582,453.

Book A is, of course, Delia’s How to Cheat at Cooking (Ebury, £20), first published in 1971 but completely re-written. Book B is Culinary Jottings for Madras by “Wyvern” (Prospect, £15), first published in 1878 but “very carefully” revised in 1885. Both authorial names are somewhat unusual. Such is Delia’s eminence that her surname only appears on the book’s copyright line. “Wyvern” is the nom-de-plume of Colonel Arthur Robert Kenney-Herbert of the Madras Cavalry. Ms Smith summarises her intention: “Without specific skills or precious time you can… produce spontaneous good food that’s fun to prepare and free from anxiety.” Putting spontaneity to one side, this is not too far from Col. Kenney-Herbert’s introductory announcement: “I address my jottings to the many who yearn to follow reform, who ‘like nice things better than nasty things’, yet have hitherto failed to penetrate the secret of success.”

Though aimed at the memsahibs of the Raj, Kenney-Herbert’s “nice things” are remarkably modern in taste. For salad dressings, he rightly insists on “a libation of the finest oil you can buy” and to “abstain from the vinegar bottle as much as possible”. Far from boiling cabbages for up to 45 minutes as specified by Mrs Beeton, he says: “Cabbages are better done in the steamer… The flavour of all green vegetables is more successfully developed by this system of cookery.” He insists that chops should “bear the mark of the grid iron”.

I wholeheartedly concur with the Colonel’s view that “ham and mustard sandwiches should make your nose tingle with mustard”, though his suggestion that when making a chicory salad “it is essential that the bowl be rubbed with garlic” brings to mind Elizabeth David’s view in her book Summer Cooking that the effectiveness of this procedure “rather depends on whether you are going to eat the bowl or the salad”. In fact, this culinary heroine very much approved of “Wyvern”: “His recipes are so meticulous and clear that the absolute beginner could follow them.”

Curiously, however, Jottings for Madras is not very useful for curry addicts. After rubbishing the curries encountered en route to the subcontinent – “The nautical curry is not, as a rule, a triumph to look back upon pleasurably with the half-closed eye of the connoisseur” – he takes a Delia line on the topic: “I strongly advocate the use of Barrie’s Madras curry powder and paste.” Sadly, my efforts to track down these condiments, both at the “Oriental Depot on the southern side of Leicester Square” and on the internet, did not bear fruit. For reasons associated with both quantity and survival, I did not attempt the Colonel’s recipe for curry powder: 8lbs coriander seed; 4lbs turmeric; 2lbs cumin seed; 1lb black pepper; 1lb dried chillies…

The author’s grasp of cavalry tactics is displayed when he tackles the ticklish problem of how to serve oysters and the requisite accompaniments simultaneously. “You sometimes see a hungry man polish off his bivalves before the lime, pepper and bread and butter have reached him. You can combat this contingency by breaking up the dishes containing these adjuncts into detachments, and serving them in two or three directions at once.” On retirement to England, this literally peppery colonel (”I strongly advise my readers not to forget to ask for a little bottle of American ‘Tabasco’, priced half a crown”) formed the Commonsense Cookery Association and became managing director of its school in 1894.

Surprisingly for a robust military man, “Wyvern” is particularly keen on hors d’oeuvres. If an officer in the Madras Cavalry sees nothing unmanly in assembling these “little dainties or kickshaws, carefully prepared and tastefully served to whet the appetite”, then the same goes for the Weasel. I carefully prepared the Colonel’s recipe for anchovy toast. Drain a tin of anchovy fillets and finely chop. Put the pulp in a bowl and stir in two raw egg yolks. Melt a tablespoon of butter in a double-boiler or bain-marie. Stir the anchovy and egg mixture into the melted butter, let it thicken and when quite hot pour over four slices of buttered toast. A subtle, delicious savoury, the snack magically whizzes you back to high tea at the height of the Raj. “Quite a revelation, not at all as salty as I was expecting,” said Mrs W, who would have made a good memsahib. “It’s very nice. Hurrah for the Colonel!” Captain Haddock, the Weasel Villas feline, also expressed great interest. These officers stick together.