Description

Peter Brears

Cooking & Dining in Medieval England

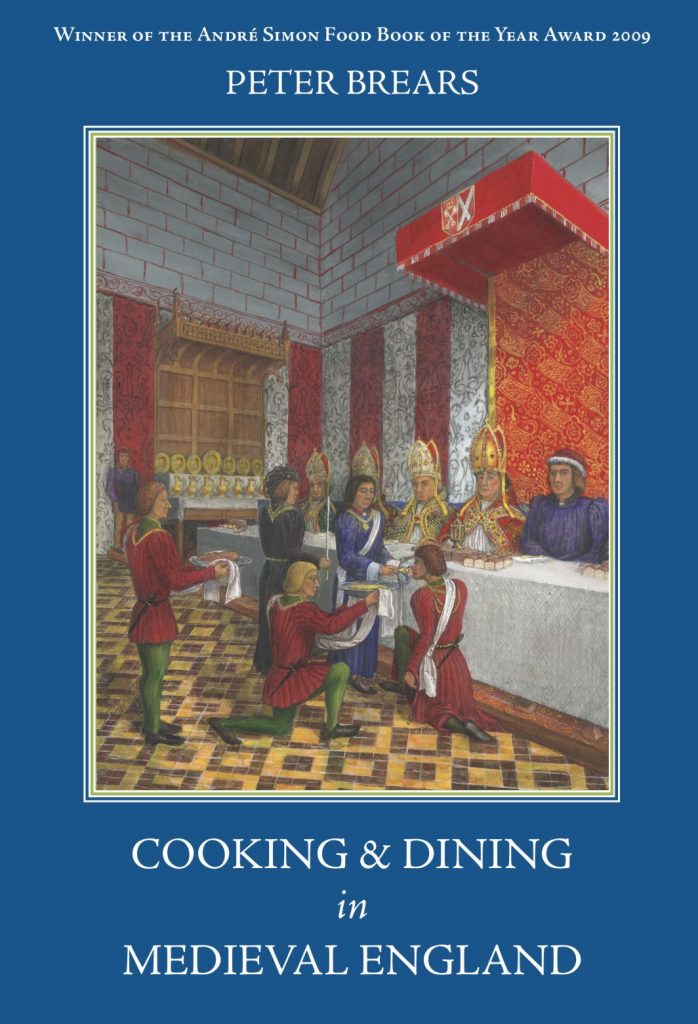

| • Winner André Simon Food Book of the Year Award 2009 • • ‘This is an important and authoritative book’, Constance B. Hieatt • • ‘A source of enlightenment and delight’, Gastronomica •This is the paperback version of the hardback we published in 2008/09. The history of medieval food and cookery has received a fair amount of attention from the point of view of recipes (of which many survive) and of the general context of feasts and feasting. It has never, as yet, been studied with an eye to the real mechanics of food production and service: the equipment used, the household organisation, the architectural arrangements for kitchens, store-rooms, pantries, larders, cellars, and domestic administration. This new work by Peter Brears, perhaps Britain’s foremost expert on the historical kitchen, looks at these important elements of cooking and dining.A series of chapters looks at the cooking departments in large households: the counting house, dairy, brewhouse, pastry, boiling house and kitchen. These are illustrated by architectural perspectives of surviving examples in castles and manor houses throughout the land. There are chapters dealing with the various sorts of kitchen equipment: fires, fuel, pots and pans. Sections are then devoted to recipes and types of food cooked. The recipes are those which have been used and tested by Peter Brears in hundreds of demonstrations to the public and cooking for museum displays. Finally there are chapters on the service of dinner and the rituals that grew up around these. Here, Peter Brears has drawn a strip cartoon of the serving of a great feast (the washing of hands, the delivery of napery, the tasting for poison, etc.) which will be of permanent utility to historical re-enactors who wish to get their details right.

To read an extract, please click here. Peter Brears was former Director of the Leeds City Museum and is one of England’s foremost authorities on domestic artifacts and historical kitchens and cooking technology. |

Review by Alex Burghart in the Times Literary Supplement (6 Mar 2013)

Peter Brears COOKING AND DINING IN MEDIEVAL ENGLAND 557pp. Prospect. Paperback, £20. 978 1 903018 87 3 Hannele Klemettilä THE MEDIEVAL KITCHEN A social history with recipes 232pp. Reaktion. £25. 978 1 86189 908 8 Throughout much of the late twentieth century British food enjoyed a famously poor reputation. As late as 2003 Jacques Chirac, President of the French Republic, scoffed that “one cannot trust people whose cuisine is so bad … . After Finland, it is the country with the worst food”. (The laugh was soon to be on him – days later the Finnish vote would send the 2012 Olympics to London rather than Paris.) The slur was not entirely without historical justification. Popular British fare took some time to recover from the two periods of food rationing, amounting to eighteen years, under which the country laboured between 1917 and 1954. This sour reputation, contends Peter Brears in Cooking and Dining in Medieval England, is a great pity. England, he says, “has one of the longest, finest and best documented cuisines”, and his captivatingly detailed book exposes something of the brilliance of its lineage. In doing so he helps to undermine the equally spurious preconception that medieval food was coarse and crude. The Hollywood images of bawdy feasts or high medieval slop (perhaps derived from the minds of Englishmen raised on the gruel of medieval public schools) are to be discarded. Both Brears and Hannele Klemettilä – who skates across the whole of continental Europe in The Medieval Kitchen: A social history with recipes – tackle this injustice and reveal the delicacy, craft and complexity that underpinned medieval food. Most of Klemettilä’s recipes, reconstructed from medieval cookbooks, are oddly familiar and might hail from any number of modish contemporary equivalents (walnut and date pie; poached eggs with mustard sauce; and partridge in ginger). Rebuilding them is no mean feat – medieval cookbooks were ordinarily simple lists of ingredients without notes or proportions – and the author’s reckonings stand up to preparation. This might have been a world ignorant of tea, coffee, chocolate and the potato, but its meats and fish, its butter and spices were very much the same. Klemettilä is, however, also good at drawing out the unusual. She has interesting digressions on extraordinary entremets (including one from the Burgundian court in which a twelve-part orchestra was brought in in a pie), early vegetarians, and the uses of tallow. Brears goes beyond food. He shows how families’ (particularly grander families’) eating habits and rituals shaped the architecture they inhabited. His fascinating dissection of Warkworth Castle’s fourteenth-century donjon shows how this ruined three-storey tower was “one of the finest concepts of efficient, sequential food preparation and management theory ever to be realised in stone”. Four staircases govern the building: one took food and fuel from ground-floor stores to the kitchen, another kegs from beer cellar to buttery, a third led guests from the entrance to the vestibule, and a fourth carried wine to the dais between Hall and chapel. (This analysis, like many others, is supported by a number of the author’s superb schematic plans and sketches.) Brears conjures up the whole operation, giving accounts of how wood was stored, fires maintained, water channelled, counting and boiling houses and kitchens designed, and food prepared. His passion for and commitment to his subject is brain-boggling and captivating (and is underscored by his having, as part of his research, served a precisely reconstructed medieval feast to a recent Archbishop of York in the York Merchant Adventurers’ fourteenth-century hall). The size of the operation required to feed the burgeoning entourages of high medieval aristocratic courts is consistently striking. The same Earl of Northumberland whose domains included Warkworth in one year purchased 123 “beefs” (at a cost of £86, or perhaps £65,000 today), 667 muttons, 160 gallons of mustard, 51lbs of pepper, 3lbs of saffron and a great deal else besides. The scale of this consumption reminds us of the huge expanse of patronage that a high medieval noble could command, and the amount of reciprocal loyalty and duty on which he, as a host, might be able to call. Food not only ordered the space behind the battlements, it kept the whole show on the road; if patronage oils the wheels of power, then it was most obviously manifested in feeding and being fed. Medieval Western European produce also exposes something about the reach of that world. This is something that neither author gives much space to, which is a shame because the presence of, for example, large quantities of pepper in English larders reveals the tentacles of a trading network stretching from northern Britain to India. Such routes were already old – when the Venerable Bede died in 735 his artefacts included pepper – as were the traditions of many of the rituals discussed. These earlier medieval antecedents are also rarely touched on, yet Europe before the twelfth century set the tone of much of what came later. The great social orchestrations of the Carolingians, for example, had a long-felt impact on European practices. Both Peter Brears’s and Hannele Klemettilä’s books put us in touch with an essential element of medieval culture and show us how it shaped that world. In helping to restore its reputation they also help to further repair the standing of an age whose rich sophistication is too often unfairly smeared.

Review by Consance B. Hieatt in Speculum (Jul 2009)

This review is from an older edition of this book. PETER BREARS, Cooking and Dining in Medieval England. Totnes, Eng.: Prospect Books, 2008. Pp. 557; black-and-white frontispiece, black-and-white figures, tables, and 1 chart. $60. Distributed by the David Brown Book Co., P.O. Box 511, 28 Main St., Oakville, CT 06779. Cooking and Dining in Medieval England surveys how food reached the kitchens of the period and was prepared and tells the modern cook how to achieve similar results: the chapter entitled ‘Pottage Recipes’ alone contains over a hundred recipes, complete with temperatures, timing, and other matters that the medieval original usually left up to the discretion of the cook. It is illustrated throughout with the author’s own drawings, showing everything from floor plans of various medieval kitchens to implements and the proper way a field-worker would cut and eat bread and cheese (‘only animals [and modern actors] bit instead of cutting or breaking their food into mouth-sized portions,’ p. 425). What is unique here is the careful description of the household arrangements for preparing and presenting food. A list of the chapter titles suggests the contents: ‘The Counting House,’ ‘Planning for Cooking,’ ‘Wood, Coals, Turves and Fires,’ ‘Water Supplies,’ ‘The Dairy,’ ‘The Brewhouse,’ ‘The Bakehouse,’ ‘The Pastry,’ ‘The Boiling House,’ ‘The Kitchen,’ ‘Kitchen Furniture and Equipment,’ ‘Pottage Utensils,’ ‘Pottage Recipes,’ ‘Leaches,’ ‘Roasting,’ ‘Frying,’ ‘The Saucery,’ ‘The Confectionery and Wafery,’ ‘Planning Meals,’ ‘The Buttery and Pantry,’ ‘The Ewery,’ ‘Table Manners,’ ‘Dining in the Chamber,’ and ‘Great Feasts.’ Note that we don’t reach the kitchen itself until almost halfway through the list! Some may wonder why the author starts at the countinghouse. The finances of feeding the many people inhabiting, or connected with, a manor house required very careful management. In any major household 100 to 150 people had to be fed, clothed, and housed. The countinghouse itself was a meeting place for a large administrative staff, including perhaps a dozen officers and clerks; pages 29–32 follow their duties throughout a long day, from 4 a.m., when the cost of the previous day’s meals was calculated and the cooks were called upon to start their day’s work, until 8 P.M., when the countinghouse closed after making sure that the day’s records were complete and accurate. The other chapters on the role of various divisions of the household are equally informative, and the explanation of how meals were planned and eaten, including the vital matter of table manners, is generally sound – although sometimes Brears seems to be drawing on very late sources. For example, he describes sugar plate as a ‘spiced icing-sugar and gum-tragacanth sugar plate,’ drawing on a recipe published in 1653, although a much simpler recipe from a manuscript of ca. 1400 is printed in a book he refers to frequently. Similarly, while Brears is probably correct that a manchet always had to weigh a pound and could not have been the ‘small dinner-bun size currently specified by some historians and used by re-enactors and in historic food displays’ (p. 116), and some late-fifteenth century illustrations of bread served at table show such loaves in the squared-off pieces Brears depicts, there are many earlier illustrations of diners with smaller round loaves (or, in some cases, round trenchers). These include the often-reproduced scene in British Library, MS Royal 14.E.lV, fol. 284r, showing John of Gaunt with two other royal personages and four bishops, with rectangular trenchers of a very dark bread plus smaller, round, white loaves. The recipes are diverse and well chosen. Directions for making roast boar’s head (pp. 168–71) should be useful for those intent on presenting that dish – but should not be attempted casually! Such enthusiasts also ought to heed Brears’s explanation (p. 34) that peacocks used for roasting should be under eighteen months old. But some of his recipes do not follow the sources exactly, as when that on page 228 for stewed collops puts all the ingredients together at once, unlike the original and despite Brears’s earlier remarks about the importance of order (p. 226), and calls for stick cinnamon and ‘bruised’ peppercorns where the original calls for ‘pouder of peper and cane!.’ Downright errors are rare, but there are some. For example, Chaucer’s Cook’s name was not ‘Roger Hodge’ (p. 212) but ‘Hodge of Ware’: ‘Hodge’ was a nickname for ‘Roger.’ On page 261 Brears suggests that beans were fried ‘for long term storage,’ which is obviously wrong. Perhaps ‘frying’ is a typographical error for ‘drying,’ but the note here (83) is incorrect and so I cannot check it. There are other flaws, such as the implication that dairy products were allowed on ember days in Lent, but, on the other hand, I am glad to find that Brears has corrected some of my own. For example, he points out something I had missed, defining ‘brawn’ as ‘boar’s meat’; apparently I had failed to check the Oxford English Dictionary on this point. In any case, he corrects enough omissions and misunderstandings to more than make up for those few matters where he himself is careless. This is an important and authoritative book.

CONSTANCE B. HIEATT, Essex, Conn.

Review by Micheal Hobbs in Gastronomica (2010)

This review is from an older edition of this book. Cooking and Dining in Medieval England Peter Brears Totnes: Prospect Books, 2008, 557 pp. Illustrations, £30 (boards) For those without a prior interest in the cooking and dining practices of medieval England, and whose notions of these subjects may have been casually acquired from movies, Peter Brears’s book will prove a source of enlightenment and delight. It is a work of great erudition that examines all aspects of domestic administration in the production and. service of food in, for the most part, large households, in which a hierarchy of officials regulated and audited everything from collecting rents, acquisition and release of ingredients and fuel, maintaining the security of storage areas, and cooking in all its separate departments, through to the elaborate etiquette for service at table. Using archaeological and architectural sources to define the disposition of various storage and work spaces, Brears sheds much light on the ergonomics, of producing food on a large scale with maximum efficiency. What also emerges is that the interpretation of archaeological remains can often be enhanced by a knowledge of cooking practices. The workings of the dairy, brewhouse, bakehouse, pastry, and boiling house are described in successive chapters, and a selection of recipes is given for each. Then follow accounts of the kitchen, kitchen furniture and equipment, and pottage utensils, with separate chapters on the products of the main kitchen organized by preparation method-pottages, leaches, roasting, and frying. It becomes clear that the level of sophistication in cooking could be very great. Well over two hundred and fifty modernized recipes are included, representative of some fifteen hundred late-fourteenth- and fifteenth-century originals. The most basic item of the medieval diet was undoubtedly bread, used also for trenchers. In the small domestic environment baking was done over the fire on a flat bakestone, or in an improvised oven inside a pot around and over which embers could be heaped. By contrast, the bakehouses of large houses had stone or brick ovens. In the medieval period pastry was essentially disposable cookware and not intended for consumption. Pre-prepared crusts were filled for baking as required for the table. Many of the pastries were recognizably similar to the tarts and flans of today, albeit using what we might consider unusual combinations of ingredients. Others were elaborately constructed. Flampoints were ornamented with pointed pieces of pastry, but most impressive of all was the castlette, comprising a round keep with four flanking round towers all being battlemented. Each tower had a separate filling, and the whole construction was served flambé at great feasts. Pottages were no more than dishes cooked in a single pot, from the simplest cereal gruels to the richest stews; the make up half the total number of recipes in the book. Meat used for a pottage might have been prepared by roasting, frying, or parboiling. Again, this was a device for facilitating its quick conversion into a range of different dishes by simmering in different stocks, with much attention being given to their consistency, texture, and color. Roasting was too time-consuming to be practiced in small households, but frying could produce food rapidly, and with little fuel consumption. Wine, wafers, and sweetmeats were served at the end of a meal. In the greatest households, where the feast was conducted as an expression of wealth, power, and status, the ostentatious culmination was the exhibition of subtleties. These were table sculptures on a particular allegorical or symbolic theme produced in the confectionery. Initially made from edible materials-sugar, marchpane, pastry-they came to be constructed from more durable ones, such as wax, paper, tinfoil, or wood. One cannot fail to be impressed by the skill and ingenuity of the medieval cook, and by the variety and sophistication of what was produced in facilities which today would be considered limited. The volume’s illustrations are either original drawings by the author or his redrawings from various sources. Although they are very informative, few are referred to in the text. For the most part they appear near where they are relevant, but it would have been helpful to have drawn attention to them. The accounts of dining in chamber, and of great feasts, both include cartoon-strip representations that are especially helpful in succinctly conveying the elaborate ceremonial involved. It is a matter of regret that this fine book is marred by inconsistencies, errors and omissions – notes, bibliography, and indices. For instance, the bibliography contains lapses in alphabetization and is incomplete, while the generally useful index of recipes bizarrely lists a recipe for vegetable pottage under ‘Beef’. The usefulness of the general index depends on readers already knowing the class of subject they are looking for; thus, ‘pimps’ and ‘shides’ are to be found only under ‘Fuel.’ Although individually trivial, the errors are cumulatively unacceptable and should have been eliminated by an attentive editor. Michael Hobbs, London

Review from Year’s Work in English Studies, Volume 89 (2010)

This review is from an older edition of this book. Peter Brears’s thick volume on Cooking and Dining in Medieval England is an informative treat, with documentary and archaeological evidence, many dozens of recipes (with imperial and metric measurement), and many drawings to illustrate features ranging from how to cook a boar’s head to how the feast for the archbishop of York’s enthronement in 1466 was served (in seventy panels). As often as possible, relevant snippets from Chaucer, Langland, Walter de Bibbesworth, Gawain and the Green Knight, Lydgate, and others are inserted into the descriptions of buildings, rooms, cooking and eating utensils, supplies, furniture, preparation, and foods. Institutional arrangements (colleges, monasteries, and so forth) are not Brears’s concern, but domestic ones are, principally those of castles and manors, with a continual eye kept on the surviving evidence for cottages. Brears begins with the counting house since household finances determine meals, and devotes individual chapters to such topics as water, the brewhouse, the bakehouse, pottage utensils, leaches, frying, the ewery, table manners, dining in the chamber, and feasts. For those of us who read texts that refer to such matters, the detailed comments with additional information are most useful.