Description

John Evelyn, Christopher Driver (ed.)

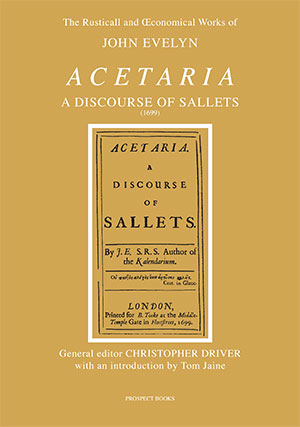

Acetaria

A Discourse of Sallets

| First published in 1699, John Evelyn’s Acetaria is an early book about food, rather than just a collection of recipes or a medical treatise – the usual forms. He discusses with immense bravura and polymathy the merits of salad, the demerits of meat-eating, the best way to mix, to grow, to gather and to season a salad, and the place of the salad in classical literature and the early history of man. What better introduction to eating more vegetables, or growing more salad plants? John Evelyn (1620-1706) was a virtuoso, scholar and man of letters of Restoration England. His diary is required reading, his architectural and environmental treatises were prophetic, and his gardening was legendary. Acetaria is one of its fruits. It has pleased generations of readers. This is a new setting of his text, with a useful introduction putting some contemporary perspectives on his opinions, together with a full index and glossary. |

Review by Helem Simpson in The Times Literary Supplement (07/97)

Contents

Foreword

Introduction

John Evelyn’s Table of Salad Plants

The Dedication

The Preface

The Plan of a Royal Garden

Errata

ACETARIA

Appendix of Recipes

The Table

Index & Glossary

Foreword

As I look at the nine volumes of the diary of Samuel Pepys, and the five of John Evelyn’s, both superbly indexed in our own time, I question how we could see or hear the period better: King Charles’s execution and the decade of the Commonwealth; the Restoration and his son’s numerous whores, created duchesses; the Royal Society, architecture and the beginnings of the Enlightenment; and not least, the food and drink, and domestic manners, of a generation of Londoners. Neither diarist would have thought the small details of their lives so imperishable after three centuries.

In beginning a short sequence of John Evelyn’s own writings on matters of food and the garden, how better to give it impetus than by re-issuing Acetaria? It encapsulates Evelyn’s ability to invest the everyday with an apparently insupportable burden of classical allusion and scholarship. Yet given a short moment of absorption and contemplation, his arguments are seductive and provoking, and his instructions clear – and well founded in practice and experience.

Just how well founded will be the more obvious when the next volume in this series is published. John Evelyn, Cook is a transcript of his manuscript recipe book, which contains the originals of many of the recipes contained in the Appendix to Acetaria.

Christopher Driver

Review by Helem Simpson in The Times Literary Supplement (Jul 1997)

John Evelyn wrote Acetaria (“a discourse of sallets”) when he was seventy-nine. He carried on undimmed well into his ninth decade, living proof of the benefits of cultivating your garden and eating your greens.

Evelyn had a practical-minded vision of creating an earthly paradise in England, and his planned great work Elysium Britanicum would have included not only Acetaria, with its meticulous calendar-scheme of planting to provide a green salad on the table every day of the year, but also Sylva (“a Discourse of Forest Trees”), his Kalendarium Hortense: or, Gard’ners Almanac, and all the Continental lessons in gardening, design, architecture, sculpture, food production and preparation acquired in the years of his self imposed exile during the Civil War.

A facsimile edition of Acetaria was published by Prospect in 1982; their new setting of his text, wrapped in a lettuce-green dust-jacket, has tidied up Evelyn’s punctuation and italics, and comes with a modest introduction by Tom Jaine (“Although every effort has been made to identify authors and works cited, the accuracy or otherwise of Evelyn’s references and quotations – he was notoriously haphazard, relying on memory – have not been tested.” Every effort, Tom?)

Acetaria is a lovely piece of writing, practical and elegant, serious and intimate, commending an ideal of salad-hood where leaves and herbs “fall into their places, like the notes in music, in which there should be nothing harsh or grating”. In his dedicatory essay to Lord Somers (“Lord High-Chancellor of England and President of the Royal-Society”), Evelyn – himself a founder member of the Royal Society – defends the slightness of his subject by describing it as “a part of natural history” adding to “solid and useful knowledge“, and pointing out how often the greatest men have “chang’d their scepters for the spade, and their purple for the gardiner’s apron”. His writing is pithy and densely packed, full of scientific curiosity – as when he describes how in foreign countries they eat the sunflower:

(e’re it comes to expand, and shew its golden face) which being dress’d as the artichoak, is eaten for a dainty. This I add as a new discovery. I once made macaroons with the ripe blanch’d seeds, but the turpentine did so domineer over all, that it did not answer expectation.

He has a swipe at Culpeper, who, less than fifty years earlier, had advised gathering salad leaves each one at its appropriate astrological hour; and is obviously concerned about precision and definition – one note for the herb-gatherer reads, “a pugil; which is no more than one does usually take up between the thumb and the next two fingers. By fascicule a rea’sonable full grip, or handful”.

Evelyn loved lists and the physical accumulation of information; Acetaria begins with a catalogue of seventy-three possible salad ingredients, describing their appearance, flavour, classical reputation, medicinal and nutritional properties. Lettuce is central, of course, “pinguid subdulcid and agreeable”, available in far more varieties than now:

for to name a few in present use: we have the alphange of Montpelier, crisp and delicate; the Arabic; ambervelleres; Belgrade, cabbage, capuchin, coss-lettuce, curled; the Genoa (lasting all winter) the imperial, lambs, or agnine, and lobbs or lop-lettuces.

Mushrooms are treated with extreme suspicion, “rank and provocative excresences” to be boiled for at least an hour “to exhaust the malignity”. He describes plants like samphire, rocket, sorrel, basil and nasturtium, which had all but disappeared from the twentieth-century British salad bowl until their revival in the past decade. This book is not merely a historic curiosity; it chimes with current culinary trends, with its defence of vegetarians as being “more acute, subtil, and of deeper penetration” than flesh-eaters, and its strikingly modern recipes like the one for a salad dressing – olive oil, aromatized wine vinegar, sea-salt, mustard, pepper and hard-boiled egg yolks.

The same cannot be said of John Evelyn, Cook. On the cover of this book is Robert Walker’s 1648 portrait of Evelyn with his hand on a human skull which, in conjunction with its title, lends an unfortunate cannibalistic air. It is a collection of recipes transcribed from an un-attributed hand-written manuscript entitled Receipts Medicinal. John Evelyn’s coat of arms and bookplate are on the binding of the manuscript, and several of the recipes are clearly embryonic versions of the recipes included at the end of Acetaria (which Evelyn there introduced as “from an experience’d housewife”). Many of the recipes are traditional, told in hobbledehoy prose peppered with “therewiths” and “if you wills” – medieval for marchpane, neats tongue pies, sullibub, liver pudding and pig brawn (“Take a great fat pig, scald him, take out all the Bones, rowle the sides as you doe brawne”, etc). This volume seems to have been a transcription by various scribes of the Evelyn family’s accumulated domestic knowledge. In his introduction, Christopher Driver, the former editor of the Good Food Guide, describes other such seventeenth-century compilations of recipes copied out by brides-to-be from the collections of their female relatives. “One can almost hear across the years the frenzied scribbling of hundreds of nubile quills on freshly ruled pages”, he writes. Nubile quill or not, John Evelyn’s words almost certainly appear in the suddenly cosmopolitan entries which occur at frequent intervals, recipes from abroad like the one for Oglio Spanish from the Spanish Ambassador of 1638-49, “Making butter a la Normande”, or for “A sort of creame taught me by a Dane”. Most of the salad and vegetable recipes seem to have been written by Evelyn too, if one goes by their condensed specificity and authoratitiveness of tone. Even so, these are notes only, unattributed and not intended for publication.

Christopher Driver’s glossary is informative on technical culinary matters. His introduction is less good, quoting “the more interesting references to food in the diary; there is another handful of no interest at all”. Odd, then, that he misses the first description of coffee-drinking in England (Evelyn’s account of a fellow student, a Greek from Crete, brewing coffee in Balliol in 1637), and also the lengthy diary entry in 1682 about the demonstration to the Royal Society by Dr Denis Papin of his new Digester (or pressure cooker). Jane Grigson, a scholarly, friendly writer after John Evelyn’s own heart, describes both these passages in her excellent chapter on the man in Food with the Famous (1979).

Both these books are interesting, but if you are buying only one, choose Acetaria. First published in 1699, it provides a suitably millennial toast “to health and long life, and the wholesomeness of the herby-diet”.