Description

Patience Gray

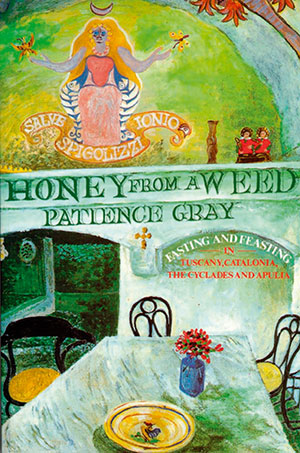

Honey from a Weed

Fasting and feasting in Tuscany, Catalonia, the Cyclades and Apulia

| This book is perhaps the jewel in Prospect’s crown. Within a few months of its first appearance in 1986 it was hailed as a modern classic. Fiona MacCarthy wrote in The Times that, ‘the book is a large and grandiose life history, a passionate narrative of extremes of experience.’ Angela Carter remarked that ‘it was less a cookery book that a summing-up of the genre of the late-modern British cookery book.’ The work has attracted a cult following in the United States, where passages have been read out at great length on the radio; and it has been anthologized by Paul Levy in The Penguin Book of Food and Drink. It was given a special award by the André Simon Book Prize committee in 1987. Currently, we publish the book in paperback, with the original drawings by Corinna Sargood and the same text in the same generous format of the original hardback. The beautiful original cover is being still being used, the goddess is Malaria, the goddess of honey from which the book takes its title. This edition is available in both Britain and the USA. Although more than a cookery book – being a musing on a life lived on the shores of the Mediterranean, particularly wherever marble suitable for sculpture can be found – it contains many vibrant and useful recipes, making it a bible for lover of Mediterranean food. Fish, wild plants, game and tomatoes are just some of the foodstuffs.

Patience Gray was first known for the 1950s classic, Plats du Jour. She shared her life with sculptor, Norman Mommens, whose appetite for marble and sedimentary rocks took them to Tuscany, Catalonia, the Cyclades (Naxos) and Apulia. These are the places which in turn inspired this rhapsodic text. Everywhere, she learned from the country people whose way of life she shared, adopting their methods of growing, cooking and conserving the staple foods of the Mediterranean. She described the rustic foods and dishes with feeling and fidelity, writing from the inside and with a deep sense of the history and continuity of Mediterranean ways. Her life in the Salento contrasted with an earlier, and indeed glittering, career in Fleet Street. Patience Gray’s first book was Plats du Jour (with Primrose Boyd, published in 1957); she then wrote a cookery book for a shipping line, The Centaur’s Kitchen with illustrations by her daughter Miranda Armour-Gray (available from Prospect Books). She described her life on Naxos in Ringdoves and Snakes and her life and work in general in Work Adventures Childhood Dreams. Patience Gray died in 2005. Corinna Sargood’s drawings, in another dimension, evoke the underlying spirit of the book, which has to do with the landscape, people, art, imagination, as much as with fasting and feasting. |

‘COOKBOOKS HELP ME ESCAPE’

‘Years before I ever stepped foot in Rome or the Chianti Valley, I traveled there by reading cookbooks… When I read Honey From a Weed, I sopped up the flavors of Patience Gray’s tales of cooking off the land while chasing marble across the Mediterranean with her sculptor beau. From a handful of single-subject books I still treasure, I spent hours learning about the regional differences in pasta sauces and the individual histories of dozens, if not hundreds, of pasta shapes I hoped to one day taste. I grew to love the hot-blooded, tradition-protecting Italian culinary sensibility I got to know through these books — so much so that I learned the language and eventually moved to the country.’ Samin Nosrat for the New York Times October 28th 2020

‘As we move into an increasingly uncertain future – a report by leading academics recently suggested that Britain is “sleepwalking” into post-Brexit food insecurity – the message of Honey From a Weed, by turns ascetic and celebratory, may come to seem more powerful still. When she wrote it, Gray knew that she was recording the past, rescuing “a few strands” from a former way of life like some social anthropologist out in the field. What she can’t have known then is that her book would also be shot through with a pungent taste of the future.’ Sheila Dillon for the Daily Mail August 20th 2017

From The Wall Street Journal:Honey From a Weed is packed with surprising little dishes so seductive it’s easy to forget how affordable they are: spring peas simmered with sliced new onions, fresh mint and olive oil; mussels stuffed with garlicky Parmesan breadcrumbs; spaghetti tossed with anchovies, preserved chillies, a bit of tomato sauce and plenty of olive oil and butter. But it’s the life lessons Ms. Gray teaches along with her kitchen craft that make “Honey From a Weed” the godmother of good-value cookbooks.

Along with recipes that feature shockingly short ingredient lists, the author chronicles her contentment with eating a plate of simply cooked vegetables and very little else for lunch or dinner. Because out-of-season, non-local produce simply didn’t exist in the places she lived, she shares ideas for feasting on the seasonal foods that are plentiful and, yes, cheapest at any given moment in the year. “A passion for youth and freshness, for grasping what the season has to give at the precise moment: This lends an ardour to daily living and eating,” she writes. And her primitive pantry demonstrates just how little you need to buy to embellish your food, when a trickle of good olive oil, a thread of wine vinegar or a sprinkle of flaky salt can make most anything taste better. The Wall Street Journal, Adina Steiman, March 2018

Financial Times July 29, 2020 Rowley Leigh

One of my pleasures in lockdown has been to spend time with my cookery books. I revisited Patience Gray’s Honey from a Weed and it taught me that my failed turnips would at least yield the boiled tops — remarkably good when doused in olive oil and dressed with a little chilli and a few anchovies. This led me to return to the obscure figure of Irving Davis, Gray’s mentor, whose A Catalan Cookery Book was put together from various notes the author had made. Financial Times, July 2020, Rowley Leigh

Cookbooks are like novels that “leave out all the other stuff,” Laurie Colwin once remarked. “There are many cookbooks by my bedside, with all the little pages turned down.” The cookbook that’s been sitting at my bedside recently is “Honey from a Weed,” by Patience Gray. First published in 1986, it documents the years in the sixties and seventies that Gray spent traversing the Mediterranean with her partner, a sculptor, in pursuit of marble. Their circumstances were such that a two-burner gas stove qualified as a luxury; outside the neolithic dwelling they occupied on Naxos, Gray stewed pots of food over driftwood and twigs. “This was ideal for summer,” she writes. “As the sea was at the door, I was able to light a fire, start the pot with its contents cooking, plunge into the sea at mid-day and by the time I had swum across the bay and back, the lunch was ready and the fire a heap of ashes. The cool of the morning—the sea rose at 5 am—was thus kept free for working.” Gray’s taxonomies of local fish and foraged weeds are admirably thorough, but I will not be making use of them. Like Colwin, I’m in it for the domestic details—the pure textures of daily life, uncomplicated by plot or character. “Honey from a Weed” is a plunge into another era’s bohemia, as evocative as Joni Mitchell singing about a guy on a Grecian isle who does the goat dance and cooks good omelettes and stews.

Molly Fischer, The New Yorker, April 2024

From the Financial Times, Jeremy Lee, 2016: Honey from a Weed is the writings of a woman who followed her man, the sculptor Norman Mommens who moved them to the Mediterranean in search of marble. In endless small steps, Patience Gray turned her back on a life in London as a journalist – she was women’s page editor of the Observer – before settling finally in a farm house in Apulia, southern Italy… The recipes are beautiful and even the alarming recipe for cooking a male fox shot in cold winter months shows humour in the rigorous personality of the author. I cook several recipes still – a dish of rabbit and prunes and a green vegetable puree amongst others. But it is the conjuring of time and place that enthrals the reader.’ Jeremey Lee, Quo Vadis. A sample page:

Solea vulgaris • family SOLEIDAE Ilenguado • (C) glóssa (G) SOGLIOLA AL VINO BIANCO CON UVA MOSCATA sole in white wine with muscat grapesOne likes to make the best of materials to hand, in this case small soles fished from the Tyrrhenian, dry white wine and muscat grapes from the vineyard at La Barozza. One sole per person and 30 g (1 oz) of butter per fish. The grapes are peeled and pipped, a handful; salt and pepper. Cut the heads off the fish, a slanting cut, clean them and strip off the skin from both sides by raising it a little where the head is severed with a sharp knife, and using a swift tearing movement – quite easy if you grasp the sole with a cloth. Leave on the lateral fins; their gelatinous nature contributes to the sauce. Sprinkle the soles with salt and pepper and put them in a sole pan with the butter and wine, about 1/4 litre for 4 small soles. Simmer on a lively heat, basting them by tilting the handle of the pan while the liquor evaporates. Add the grapes. At a certain moment the wine, the butter and the juices of the soles unite into the consistency of a perfect sauce. Culinary miracles happen by evaporation. Serve at once.

A review of Honey from a Weed by Eddie Lakin, retrieved from the WWW at <http://cookingandeatinginchicago.blogspot.com/2009/01/classic-cookbook-review-honey-from-weed.html>

I’m constantly reading reviews of the latest and the greatest cookbooks on various blogs and foodie sites, but no one seems to be paying much attention to the old classics. That’s too bad, because there are just hundreds of great old cookbooks rattling around out there at used book stores (both brick and mortar and online), and you can stock up on wonderful food writing for three, four, and five bucks a shot. Don’t wait for re-issues. Go back to the originals. They’re great. Anyway, that’s a brief intro and justification for a series of posts I’m going to dedicate to reviewing classic old (call’em vintage, even) cookbooks in my collection. I had a serious used-bookstore addiction during my line cook days and, much to my wife’s chagrin, my books got shuttled around in boxes for a while until we had enough shelf space to accommodate them. Some are classic, in the true old-school French sense, some are funny in the 60’s-70’s what-were-they-thinking sense, and some are just as on point and topical today as they were when they were written. This review falls into that latter category.

Honey from a Weed; Fasting and Feasting in Tuscany, Catalonia, The Cyclades, and Apulia, by Patience Gray.

This book was originally published in 1986, and it details twenty years of the author’s life that she spent living in various locales while accompanying her sculptor husband as he went to work where he could find certain stones; “It is of course entirely owing to the Sculptor’s appetite for marble and stone,” she writes, “that this work came into existence in the first place, and that I am held in the mysterious grip of olive, lentisk, fig, and vine”. Gray is British and the book chronicles her experiences eating and cooking while mostly living in very rustic areas during the 60’s and 70’s, far from any sign of tourism or modernity. She often cooks over open fire, without the benefit of refrigeration, and describes some very challenging situations. The food, therefore, is rustic. It’s the everyday fare of the peasants, farmers, fishermen, and others who she encounters, and, for this reason, the book is not only a cookbook, but a reminiscence of the people she meets and gets to know and, even more, for their lifestyle, which, even 30-40 years ago, Gray was insightful enough to recognize was in danger of being forgotten as more and more harbingers of modern, industrial life crept in.

‘Poverty rather than wealth gives the good things of life their true significance. Home-made bread rubbed with garlic and sprinkled with olive oil, shared–with a flask of wine–between working people, can be more convivial than any feast. My ambition in drawing in the background to what is being cooked is to restore the meaning. I also celebrate the limestone wilderness. If I stress the rustic source of culinary inspiration, it is not in opposition to the scientific… In my experience it is the countryman who is the real gourmet and for good reason; it is he who has cultivated, raised, hunted, or fished the raw materials and has made the wine himself. The preoccupation of his wife is to do justice to his labours and bring the outcome triumphantly to table. In this an emotional element is involved. Perhaps this very old approach is beginning to once again inspire those who cook in more urban situations. In my view it was not necessarily the chefs of prelates and princes who invented dishes. Country people and fishermen created them, great chefs refined them and wrote them down.’

This book is way ahead of its time. Gray presages recent trends of nose-to-tail eating, eating seasonally, foraging, all-things-pork, local eating, and canning/preserving. Of course, that’s because these “trends” aren’t really new or trendy at all, but are simply an indication that within our modern urban enclaves, we’ve become so removed from these centuries-old building blocks of cuisines, that the re-introduction of them by current chefs within the context of contemporary restaurants appears novel. It’s a painstakingly thorough book as well. There are ten or twelve chapters dedicated to specific dishes or foodstuffs (”Beans, Peas, and Rustic Soups”, “Edible Weeds”, “La Polenta”), but there are also chapters that focus on equipment (”Pots and Pans”) or techniques (”Chopping and Pounding”). There’s also a massive bibliography and a great cross-referenced index. There’s a ton of information here. And it’s good stuff, but the real lure is Gray’s celebratory prose, which really serves to get at the root of these cuisines, to allow the reader to understand terms like cacciatora and marinara in terms of where they came from, and how the dish evolved directly from what the people who prepared it were doing all day. Classic French provincial cuisine, Tuscan cooking, Catalan cuisine–these traditions all came directly from centuries of people living and working in these regions, and Gray lived and worked among them.

‘The princely life of the Mantuans has been obliterated by time, malaria, and the Austrian occupation, leaving only its shell. Oblivious to this, farmers from the countryside come into town and are found imbibing a dense bean soup at ten in the morning in the trattorie underneath the arcades of the Palazzo della Ragione which towers over the marketplace. The shops are stuffed with gigantic hams; every kind of smoked and fresh sausage; coppa, smoked loin of pork in the form of a large sausage closely bound with string; bondiola, a smoked boiling sausage round in shape; musetti con lingua, made from pig’s snout and tongue; lardo, salted pig’s fat cut from its rump; capelli dei preti also called triangoli, small triangles of stitched pork skin stuffed with sausage meat, then smoked, for boiling; and nuggets of smoked pork strung together to be flung into the soup. In agricultural areas where communications are spasmodic, the pig figures as the winter saviour of mankind. Its products can be kept at hand without deterioration, and, if not of domestic manufacture, can be acquired on weekly trips to town. The fact that pork is indigestible gives a greater significance here to game in autumn. It also throws vegetables into a relief, the green leafy ones, spinach, spinach beet, cicoria ‘Catalogna’; the astringent artichoke and cardoon; and most particularly, those root vegetables whose virtue lies in a certain bitterness–root chicory, salsify, scorzonera, and black radishes. All are ritually prepared to offset the ill effects of the delicious products of the pig. One can cultivate a better acquaintance with these roots by growing them.’

At its heart, this book is more a monument to a more simple lifestyle than it is a condemnation of our current-day lives of everything-all-the-time excess. But as someone living in a large city, eating in ever more impressive restaurants, and especially with the advent of the internet broadcasting (and selling) the biggest and best of everything 24/7, it’s hard to read about these simple rustic ways and not come to wonder if this sort of excess (and excess to the point that we’ve become blase about it) isn’t detrimental to our physical and mental well-being. She touches on this phenomenon as well, which, even then had begun to rear it’s modern head, alluding to the recent trend of looking at stare bene–the concept of living well–as being more tied to income than quality of life, and noting with wonder the availability of out of season vegetables and “industrially reconstituted protein”, relegating them to the stuff of Marie Antoinette-level luxuries. And, as in much of the book, she manages to distill this idea down to one pithy local saying. In the midst of her “parting salvo” about the current and future state of food, Gray describes an anecdote about what people who come to Spigolizzi in the summer can be heard to exclaim:

‘Qui c’e un vero paradiso’ (Here is a real paradise) and the locals reply ‘Ma l’inferno purtroppo e tanto piu comodo!’ (Yes, but Hell is so much more convenient!)

Patience Gray died in 2005, but she left behind an amazing and timeless memoir, cookbook, and treatise on food in the form of Honey from a Weed. Buy it instead of that Rachel Ray book you might impulsively grab the next time you’re at the bookstore.